FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 21

The Rise of the Originate-

to-Distribute Model

and the Role of Banks in

Financial Intermediation

1.Introduction

istorically, banks used deposits to fund loans that they

then kept on their balance sheets until maturity. Over

time, however, this model of banking started to change. Banks

began expanding their funding sources to include bond

financing, commercial paper financing, and repurchase

agreement (repo) funding. They also began to replace their

traditional originate-to-hold model of lending with the so-

called originate-to-distribute model. Initially, banks limited

the distribution model to mortgages, credit card credits, and

car and student loans, but over time they started to apply it

to corporate loans. This article documents how banks adopted

the originate-to-distribute model in their corporate lending

business and provides evidence of the effect that this shift has

had on the growth of nonbank financial intermediation.

Banks first started “distributing” the corporate loans they

originated by syndicating loans and also by selling them in the

secondary loan market.

1

More recently, the growth of the

market for collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) has provided

1

In loan syndications, the lead bank usually retains a portion of the loan and

places the remaining balance with a number of additional investors, usually

other banks. This arrangement is made in conjunction with, and as part of,

the loan origination process. In contrast, the secondary loan market is a

seasoned market in which a bank, including lead banks and syndicate

participants, can subsequently sell an existing loan (or part of a loan).

banks with yet another venue for distributing the loans that

they originate. In principle, banks could create CLOs using the

loans they originated, but it appears they prefer to use collateral

managers—usually investment management companies—that

put together CLOs by acquiring loans, some at the time of

syndication and others in the secondary loan market.

2

Banks’ increasing use of the originate-to-distribute model

has been critical to the growth of the syndicated loan market,

of the secondary loan market, and of collateralized loan

obligations in the United States. The syndicated loan market

rose from a mere $339 billion in 1988 to $2.2 trillion in 2007,

the year the market reached its peak. The secondary loan

market, in turn, evolved from a market in which banks

participated occasionally, most often by selling loans to other

banks through individually negotiated deals, to an active,

dealer-driven market where loans are sold and traded much

like other debt securities that trade over the counter. The

volume of loan trading increased from $8 billion in 1991 to

$176 billion in 2005.

3

The securitization of corporate loans also

experienced spectacular growth in the years that preceded the

financial crisis. Before 2003, the annual volume of new CLOs

issued in the United States rarely surpassed $20 billion. After

2

According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association,

97 percent of corporate loan CLOs in 2007 were structured by financial

institutions that did not originate the loans.

Vitaly M. Bord and João A. C. Santos

Vitaly M. Bord is a former associate economist and João A. C. Santos

a vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Correspondence: joao.santos@ny.frb.org

The authors thank Nicola Cetorelli, Stavros Peristiani, an anonymous reviewer,

and participants at a Federal Reserve Bank of New York seminar for useful

comments. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal

Reserve System.

H

22 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

that, loan securitization grew rapidly, topping $180 billion

in 2007.

Investigating the extent of U.S. banks’ adoption of the

originate-to-distribute model in corporate lending has proved

difficult because of data limitations. Thomson Reuters Loan

Pricing Corporation’s DealScan database, arguably the most

comprehensive data source on the syndicated loan market and

the source used by many researchers in the past, imposes

serious limitations on the investigation of this issue. This

database includes information available only at the time of loan

origination, making it impossible to use it to investigate what

happens to the loan after origination. Furthermore, DealScan

has very limited information on investors’ loan shares at the

time of origination. The information on the credit shares

that each syndicate participant holds is sparse, and even the

information on the share that the lead bank—the bank that sets

the terms of the loan—retains at origination is missing for

71 percent of all DealScan credits.

The Loan Syndication Trading Association database

contains micro information on the loans traded in the

secondary market, but it has no information about the identity

of the seller(s) or buyer(s), ruling out its use to close the

information gaps in DealScan. Financial statements filed with

the Federal Reserve, in turn, contain information only on the

credit that banks keep on their balance sheets and thus cannot

be used to ascertain the volume of credit that banks originate.

These statements contain information on the loans that banks

hold for sale, but, as Cetorelli and Peristiani (2012) explain in

detail elsewhere in this volume, this variable provides limited

information on the extent to which banks have replaced the

originate-to-hold model with the originate-to-distribute

model in their lending business.

4

We rely instead on a novel data source, the Shared National

Credit program (SNC) run by the Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Like

DealScan, the SNC program is dominated by syndicated loans.

In contrast to DealScan, however, the SNC program tracks

3

Researchers have suggested several explanations for the development of the

secondary market, including the capital standards introduced with the 1988

Basel Accord (Altman, Gande, and Saunders 2004), the standardization of

loan documentation and settlement procedures that came about with the

establishment of the Loan Syndication Trading Association in 1995 (Hugh and

Wang 2004), and the increase in demand and liquidity resulting from the

increasing involvement of institutional investors (Yago and McCarthy 2004).

See Gorton and Haubrich (1990) for a detailed description of the loan-sales

market in the 1980s.

4

This variable does not distinguish corporate loans from all the other loans

that banks may intend to sell. Further, since there is no information on when

the loans held for sale were originated, ascertaining banks’ relative use of the

originate-to-distribute model based on this variable is difficult. Lastly, the

variable reports only the loans that banks “intend” to sell, not the actual

loans that they sold.

loans over time, and it has complete information on investors’

loan shares over the life of the credit. We discuss the SNC

database in more detail in the data section.

Our study of the change in banks’ corporate lending model

yields a number of significant findings. Although the data

indicate that lead banks increasingly used the originate-to-

distribute model from the early 1990s on, we conclude that this

increase was limited to a large extent to term loans; in their

credit-line business with corporations, banks continued to rely

on the traditional originate-to-hold model. Further, we find

that lead banks increasingly “distributed” their term loans by

selling larger portions of them not only at the time of the loan

origination, but also in the years after origination. For example,

in 1988, the first year of our sample, lead banks retained in

aggregate 21 percent of the term loans they originated that year.

In 2007, lead banks retained only 6.7 percent of the term loans

originated in that year. By 2010, lead banks had managed to

further lower their share in the credits they had originated in

2007 to 3.4 percent.

Our investigation into the entities investing in bank loans

confirms that other banks were not quick to step in and take

over as lead banks reduced their stake in the loans they

originated. Instead, we find that new loan investors, including

investment managers and CLOs, increasingly assumed

control of the credit business. In 1993, all together, nonbank

investors acquired 13.2 percent of the term loans originated

that year. In 2007, they acquired 56.3 percent of the term

loans originated in that year, a 327 percentage point increase

from fifteen years earlier.

The trends documented in this article have important

implications. Banks’ increasing use of the originate-to-

distribute model in their term-lending business will lead to a

transfer of important portions of credit risk out of the banking

system. In the process, however, it will contribute to the growth

of financial intermediation outside the banking system,

including a larger role for unregulated “shadow banking”

institutions.

5

It will also, over time, make the credit kept by

banks on their balance sheets less representative of the still-

essential role they perform in financial intermediation.

In addition, banks’ increasing use of the originate-to-

distribute model could lead to some weakening of lending

standards. According to several theories—including those of

Ramakrishnan and Thakor (1984), Diamond (1984), and

Holmström and Tirole (1993)—banks add value because of

their comparative advantage in monitoring borrowers. To

carry out this task properly, banks must hold the loans they

originate until maturity. If they instead anticipate keeping only

a small portion of a loan, their incentives to screen loan

5

See Pozsar et al. (2010) for a detailed account of the growth of shadow

banking in the United States.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 23

applicants properly and to design the terms of the loan contract

will diminish.

6

They will also have less incentive to monitor

borrowers during the life of the loan.

7

The growth of the

CLO business has likely exacerbated these risks because

CLO investors invest in new securities that depend on the

performance of the “reference portfolio,” which is made up

of many loans, often originated by different banks.

8

Banks’ adoption of the originate-to-distribute model may

also hinder the ability of corporate borrowers to renegotiate

their loans after they have been issued.

9

This difficulty may

arise not only because the borrower will have to renegotiate

with more investors but also because the universe of investors

acquiring corporate loans is more heterogeneous.

Finally, our evidence that banks continue to use the

traditional originate-to-hold model in the provision of credit

lines supports the argument that banks retain a unique ability

to provide liquidity to corporations, possibly because of their

access to deposit funding.

10

Our findings are in line with the

theories advanced by Holmström and Tirole (1998) and

Kashyap, Rajan, and Stein (2002) concerning banks’ liquidity

provision to corporations. Still, as Santos (2012) documents,

banks’ provision of liquidity to depositors and corporations

exposes them to a risk of concurrent runs on both sides of their

balance sheets.

The remainder of our article is organized as follows.

The next section presents our data and methodology and

characterizes our sample. Section 3 documents U.S. banks’

transition from the originate-to-hold model to the originate-

to-distribute model in corporate lending over the past two

decades. Section 4 identifies the relative role of the various

investors that increasingly buy the credit originated by

banks. Section 5 summarizes our findings and their larger

implications.

6

See Pennacchi (1988) and Gorton and Pennacchi (1995) for models that

capture these moral hazard problems.

7

Recent studies, including Sufi (2007), Ivashina (2009), and Focarelli, Pozzolo,

and Casolaro (2008), document that lead banks in loan syndicates use the

retained share to align their incentives with those of syndicate participants

and commit to future monitoring.

8

See Bord and Santos (2010) for evidence that the rise of the CLO business

contributed to riskier lending.

9

Borrowers often renegotiate their credits to adjust the terms of their loans

(Roberts and Sufi 2009) or to manage the maturity they have left in their credits

(Mian and Santos 2011).

10

See Gatev, Schuermann, and Strahan (2009) and Gatev and Strahan (2006)

for empirical evidence in support of banks’ dual liquidity role to depositors

and corporations.

2. Data, Methodology, and Sample

Characterization

2.1 Data

Our main data source for this project is the Shared National

Credit program, run by the Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation, the Federal Reserve Board, and the Office

of the Comptroller of the Currency. At the end of each year,

the SNC program gathers confidential information on all

credits that exceed $20 million and are held by three or more

federally supervised institutions.

11

For each credit, the SNC program reports the identity of the

borrower, the type of the credit (term loan or credit line, for

example), purpose (such as working capital, mergers, or

acquisitions), amount, maturity date, and rating. In addition,

the program reports information on the lead arranger and

syndicate participants, including their identities and the share

of the credit they hold.

The SNC data fit nicely with our goal of investigating

the role that banks continue to play in the origination of

corporate credit in the United States and the role they have

played in the growth of financial intermediation outside the

banking system. Since the SNC program gathers information

on each syndicated credit at the end of every year, we can link

credits over time and determine the portion of each credit

that stays in the banking sector and the portion acquired by

nonbank financial institutions both at the time of the credit

origination and in each subsequent year during the life of

the credit. In addition, since we have this information over

the past two decades, we can investigate how the relative

importance of the various players in the syndicated loan

market has evolved over time.

We complement the SNC data with information from the

Moody’s Structured Finance Default Risk Service Database and

from Standard and Poor’s Capital IQ. The Moody’s database

has information on structured finance products, including the

size, origination date, and names. We rely on the Moody’s

database to identify CLOs among the syndicate participants

reported in the SNC program that do not have the letters CLO

in their names. We use the Capital IQ database to identify

private equity firms, hedge funds, and mutual funds among

the syndicate participants.

11

The confidential data were processed solely within the Federal Reserve

for the analysis presented in this article.

24 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

2.2 Methodology

Our investigation into the effect of the originate-to-distribute

model on the importance of banks in financial intermediation

has two parts. We begin by investigating how the rise of that

model affected the portion of each credit that the lead bank

retains during the life of the credit. To this end, for each credit

in the SNC program, we first compute the portion that the lead

bank retains on its balance sheet at origination. Next, because

banks sometimes sell or securitize part of their credits after they

originate them, we compute the portion of the credit that the

lead bank still retains on its balance sheet three years after the

origination year.

In the second part of our investigation, we identify the

buyers of bank credits and how the role of the various buyers

has changed over the past two decades. For each credit, we

compute the portion that the lead bank sells to other banks

and the portion that it sells outside the banking sector,

distinguishing in the latter case whether the acquiring

institution is an insurance company, a finance company, a

pension fund, an investment manager, a private equity firm,

a CLO, or a broker or investment bank. This part of our

investigation allows us to pin down the role that banks have

played in the growth of financial intermediation outside the

banking system in general and their role in the growth of

shadow banking in particular.

Because the nature of the credit contract may affect

the lead bank’s ability to sell or securitize the credit, we

distinguish between term loans and credit lines throughout

our investigation. For a similar reason, we also categorize the

credits according to their purpose: that is, whether they are

to fund mergers and acquisitions or capital expenditures

or whether they are to serve corporate purposes.

2.3 Sample Characterization

Our sample covers the period 1988-2010. On average, we

observe 7,432 credits each year. Of these, 1,758 are new credits

originated in the year, and 5,674 are credits originated in prior

years. Even though the criteria for inclusion of a credit in the

SNC program remained unchanged throughout the sample

period, inflation and growth over the past two decades

contributed to an upward trend in the number of credits in the

SNC database. In 1989, the SNC database had 5,402 credits, of

which 1,368 were originated in that year. In 2007, at the peak

of the business cycle, it had 8,248 credits, of which 2,114 were

originated in that year.

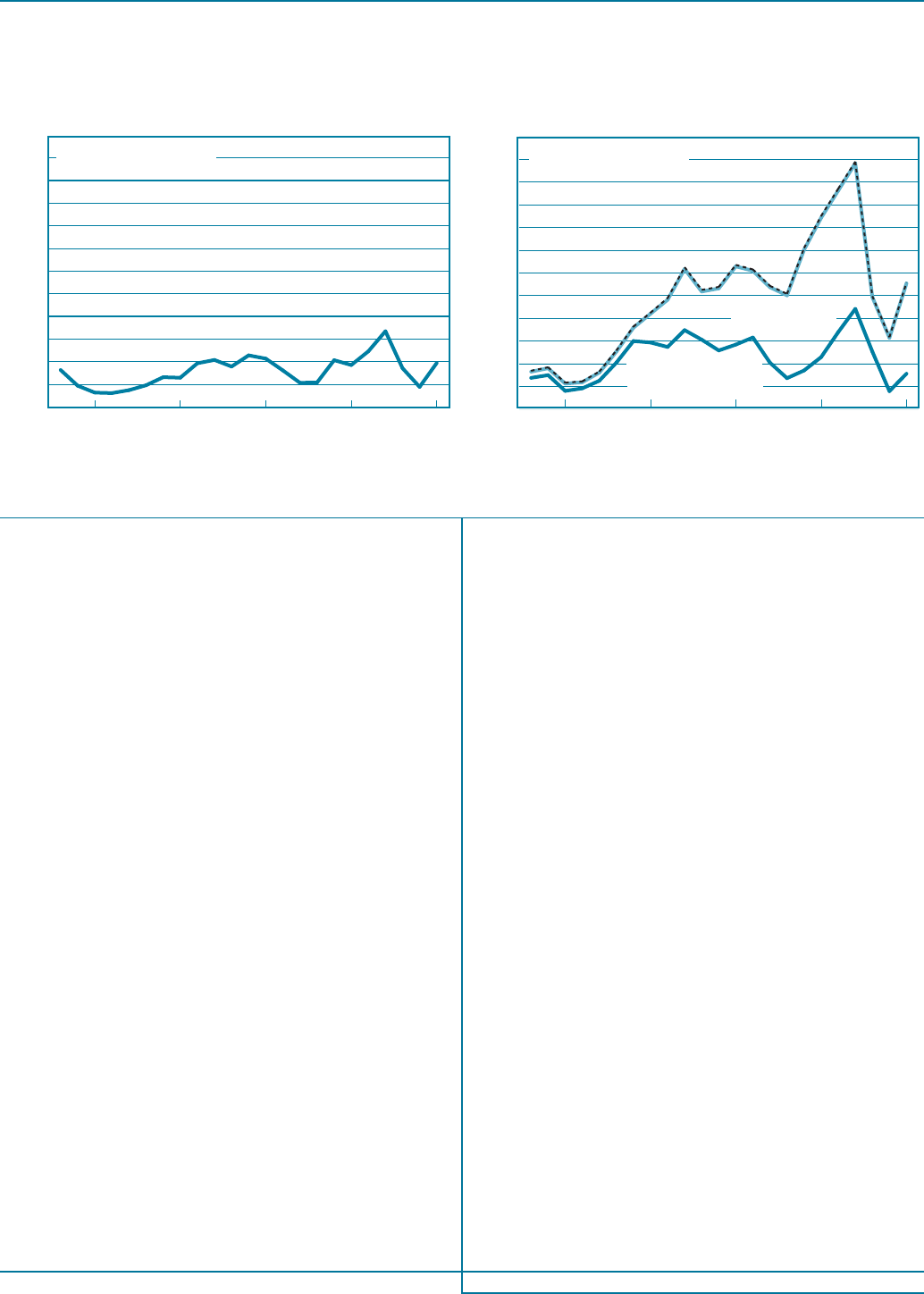

To get a better sense of the SNC database coverage, we

compare the annual value of credits included in that database

with the annual value of credits in DealScan, the database

mentioned above that has been extensively used for research on

bank corporate lending in recent years.

12

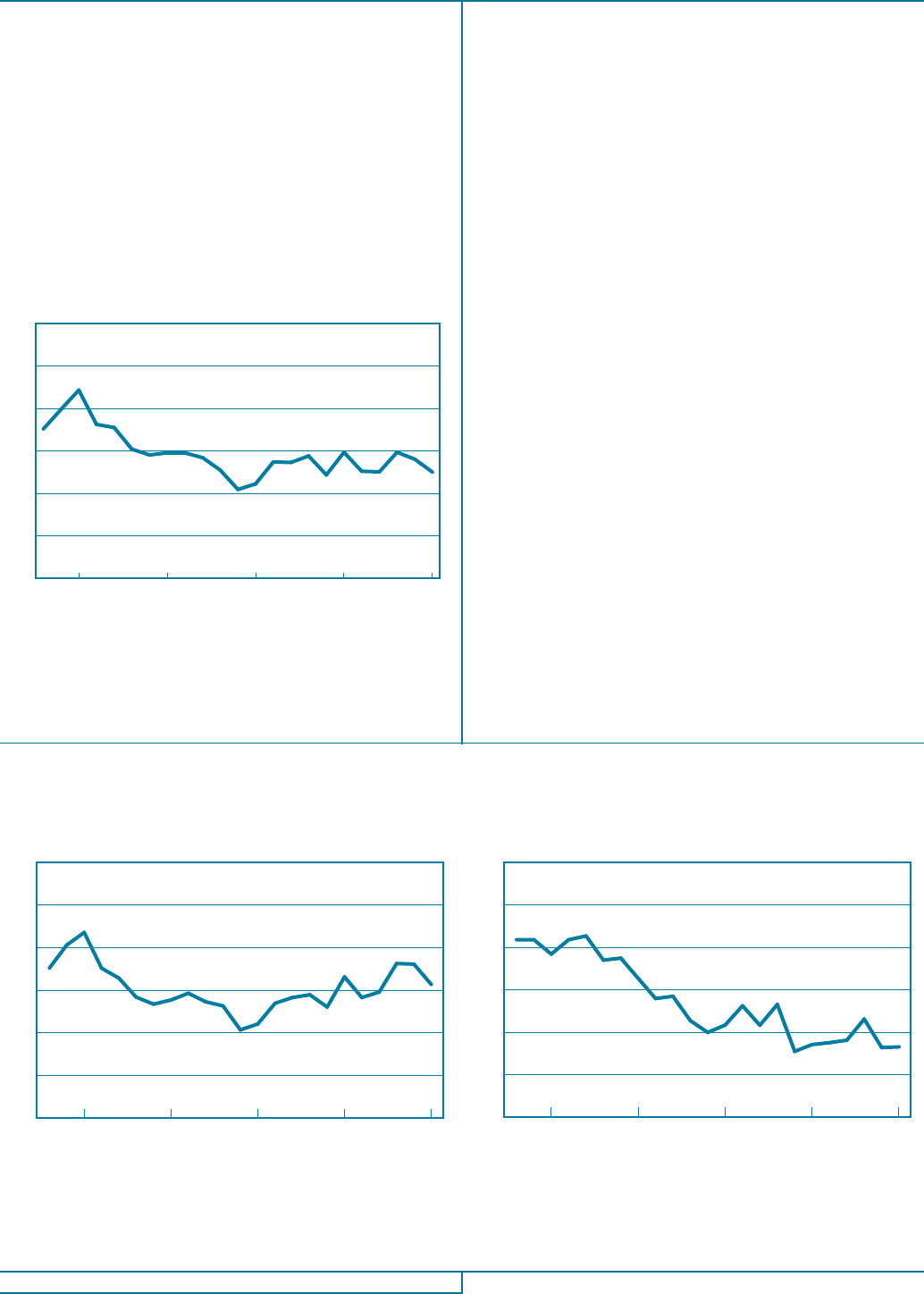

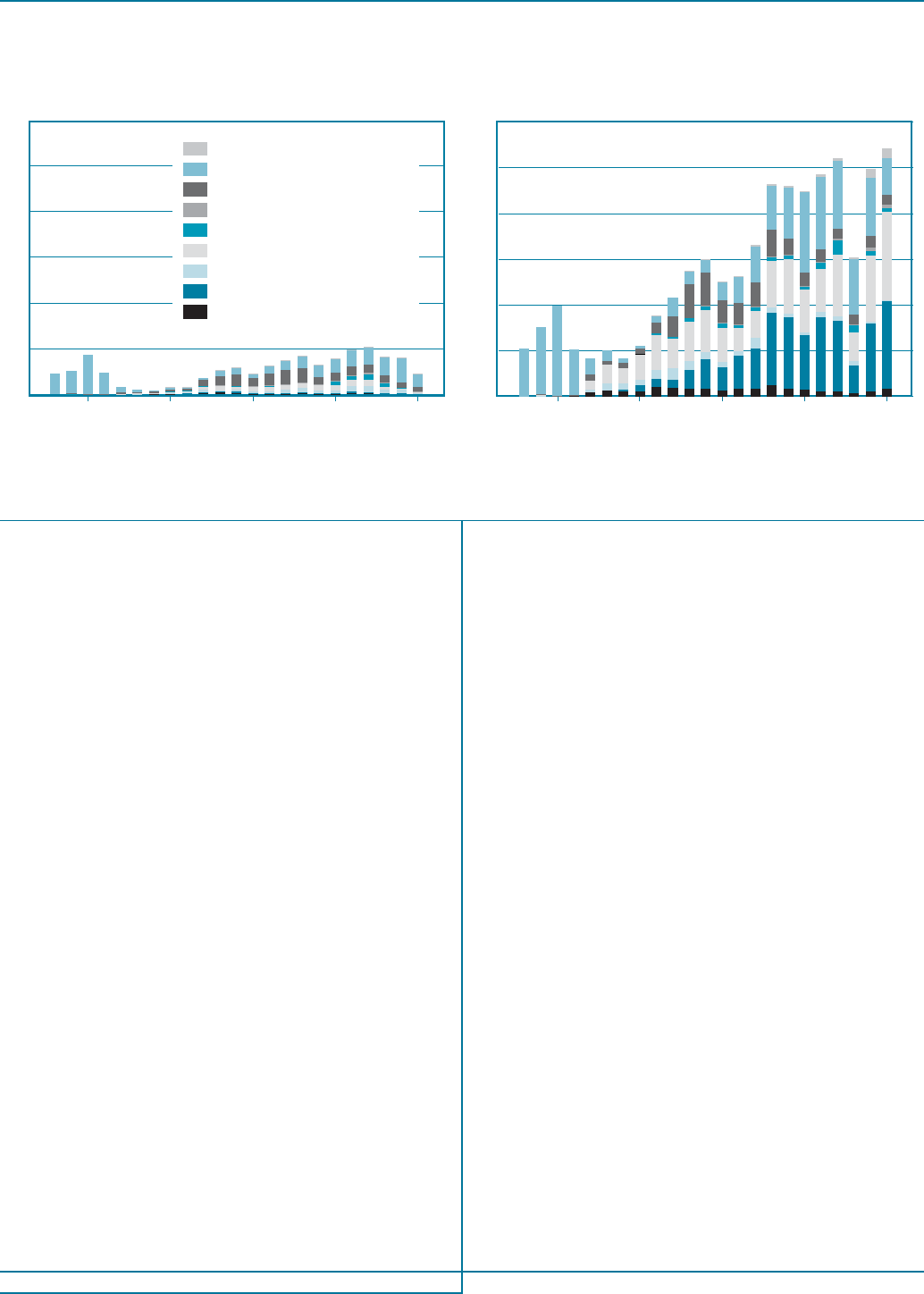

Chart 1 reports the

annual value of new credits—that is, credits originated in each

year—in the SNC database and the annual value of credits

reported in DealScan. Since SNC covers only credits above

$20 million, we also report the annual value of credits in

DealScan above that threshold. To make the information from

the two databases even more comparable, we further adjust the

information reported from DealScan by excluding credits that

are classified as “restatements” of previous credits, since this

indicates a renegotiation of an existing credit.

13

From Chart 1, it is apparent that both databases pick up the

positive trend in the volume of credit as well as the effect of the

three recessions in the United States during the sample period

(1990-91, 2001, and 2008-09). It is also clear that the main

difference between the two databases is that DealScan reports

information on new credits as well as information on renegoti-

ations of existing credits. The fact that SNC reports only credits

above $20 million while DealScan contains information on

credits above $100,000 does not constitute an important

difference between the two databases. When we adjust the

information reported in DealScan to “match” the credits

reported in the SNC database, the difference between the

two databases becomes very small. On average, each

year the volume of credit reported in the SNC database

is 37.2 percent of that reported in DealScan. When we restrict

the credits in DealScan to those above $20 million, that share

increases to 37.8 percent; when we further drop renegotiations

from DealScan, the share rises to 74.4 percent.

12

Examples of papers that use DealScan include Dennis and Mullineaux

(2000), Hubbard, Kuttner, and Palia (2002), Santos and Winton (2008, 2010),

Hale and Santos (2009, 2010), Sufi (2007), Bharath et al. (2009), Santos (2011),

Paligorova and Santos (2011), and Bord and Santos (2011).

13

In SNC, renegotiations do not usually give rise to a new credit, while in

DealScan they do.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 25

Chart 1

Loan Volumes Reported in the SNC and DealScan Databases

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

Billions of U.S. dollars

SNC Issuance by Year

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

LPC Issuance by Year

Billions of U.S. dollars

All loans

Sources: Shared National Credit (SNC) database, produced jointly by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; DealScan database, produced by Thomson Reuters Loan Pricing Corporation (LPC).

2,200

1,800

1,400

1,000

600

200

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

2,200

1,800

1,400

1,000

600

200

Loans of greater than

$20 million, excluding

renegotiations

Loans of greater

than $20 million

3. From Originate-to-Hold

to Originate-to-Distribute

In traditional banking, banks originate credits and hold them

on their balance sheet until their maturity. Over time, however,

banks began to replace the originate-to-hold model with the

originate-to-distribute model, whereby they originate a credit

and sell or securitize a portion of it at the time of origination or

later. In this section, we investigate how the adoption of the

originate-to-distribute model reduced the exposure of banks

to the credits they originated over the past two decades.

3.1 Distribution at the Time of Credit

Origination

To investigate the effect of the originate-to-distribute model

on the exposure of banks to the credits they originate, we begin

by looking at the lead banks’ market share of the credits they

originate, at the time of the credit origination.

For our purposes, “banks” are all institutions that are

regulated and that perform the traditional bank roles of

maturity and credit transformation. Thus, the banks discussed

throughout our article refer to all commercial banks, bank

holding companies (BHCs), thrifts and thrift holding

companies, credit unions, and foreign banking organizations,

including their domestic branches. Note that whether an

institution is classified as a bank may vary over time. For

example, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs are classified as

banks only from January 1, 2009, when they became BHCs. For

the period preceding this date, they are not counted as banks

since they were operating as investment banks.

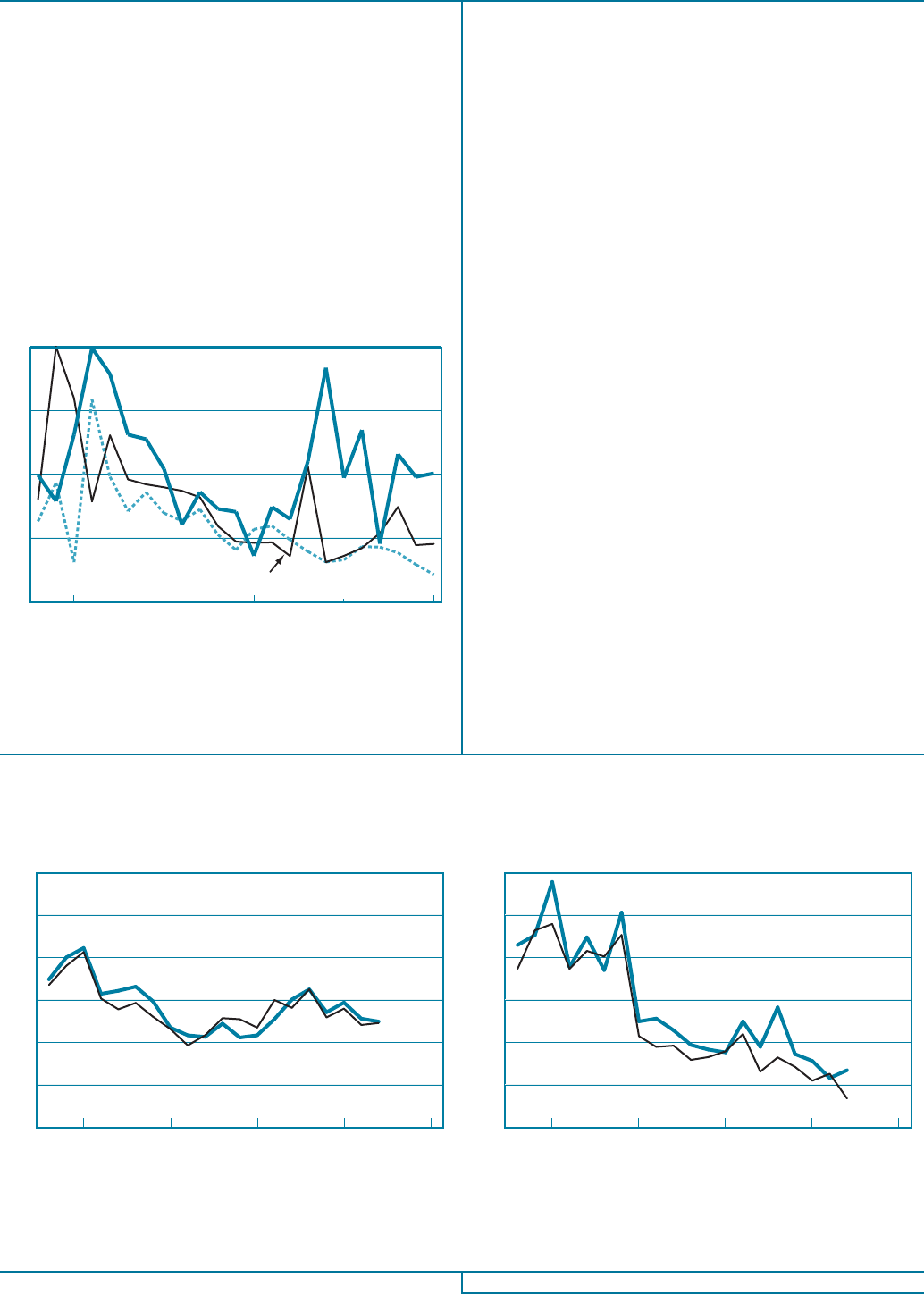

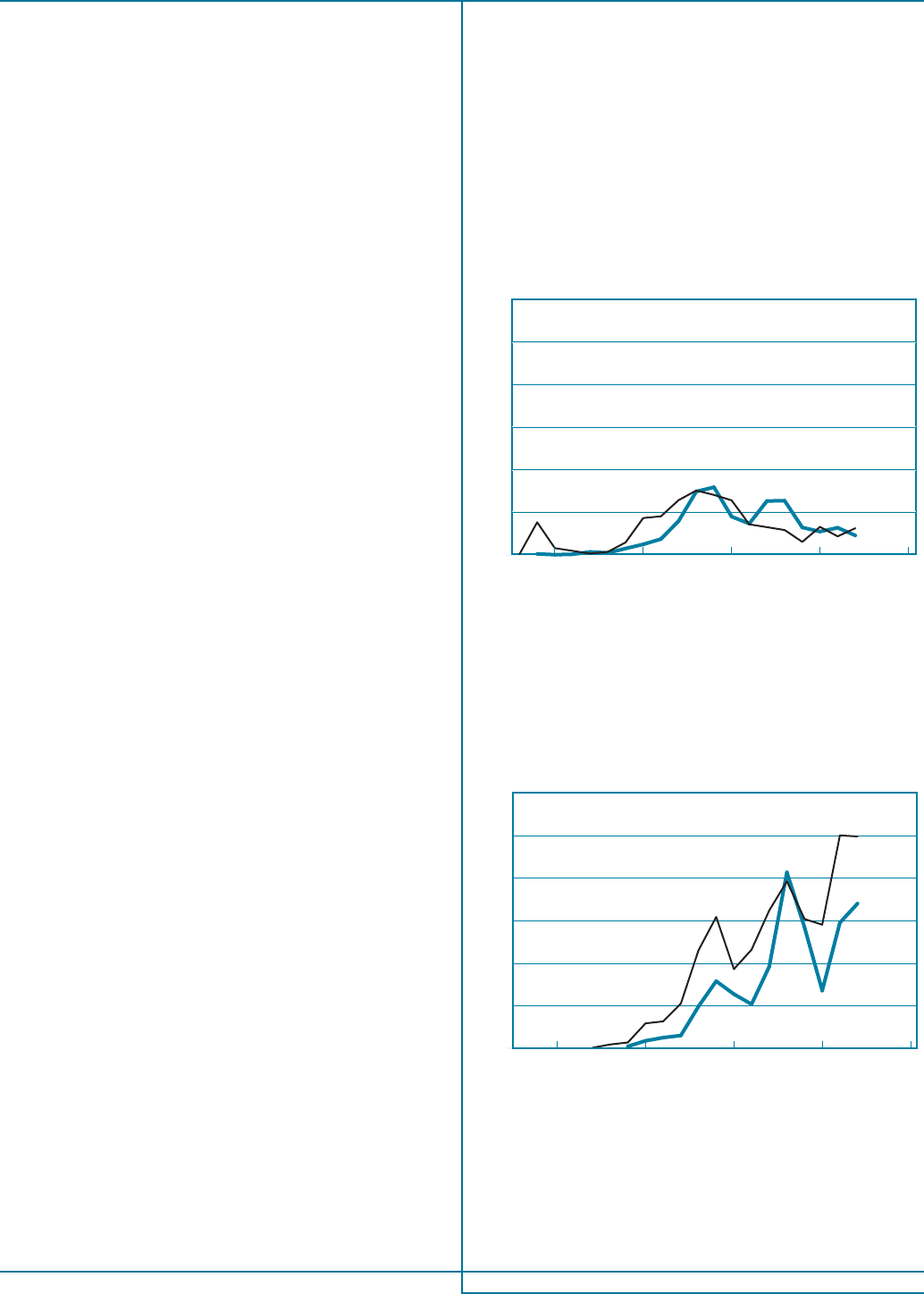

In 1988, the first year of the sample period, lead banks

retained in aggregate a stake of 17.6 percent of the credits they

originated in that year, including term loans and credit lines

(Chart 2).

14

Beginning in 1990, when they retained in aggregate

22.2 percent, lead banks started to decrease their share of the

credits they originated, reaching a low of 10.5 percent in 1999.

During the 2000s, the aggregate shares varied with the business

cycle but generally remained steady at around 13 percent.

The market share of the credits that lead banks retain at

origination has clearly fallen, but the representation of this

decline in Chart 2 is skewed by the large number of credit lines

in our sample. As we can see from Chart 3, while banks have

increasingly replaced the originate-to-hold model with the

originate-to-distribute model over the past two decades, this

substitution has been far more pronounced in the origination

of term loans than of credit lines. To be sure, this difference was

not immediately apparent: In 1988, lead banks retained in

aggregate 17.6 percent of the credit lines and 21 percent of the

14

Here, and throughout the rest of the article, we use the terms market share

and aggregate share interchangeably. By lead banks’ market or aggregate share,

we mean the share of all credits that the lead banks, taken together, retain.

It is computed as the sum of all the lead banks’ retained credit amounts

divided by the sum of all new credits they originated that year.

26 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

Chart 2

Lead Banks’ Market Share of Syndicated Loans

at Credit Origination

0.25

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.30

0.15

0.20

0.10

0

0.05

Chart 3

Lead Banks’ Market Share of Credits at Origination, by Credit Type

Market share

0.25

Credit Lines

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.30

0.15

0.20

0.10

0

0.05

0.25

0.30

0.15

0.20

0.10

0

0.05

Term Loans

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

term loans they extended in that year. These shares declined

to 10.3 percent and 10.0 percent, respectively, by 1999.

However, in the first decade of the 2000s, while lead banks

continued the trend of decreasing their market share of term

loans, they reversed the trend for credit lines. By 2006, the last

year before the data pick up the effects of the most recent

financial crisis, lead banks increased their market share of the

credit lines they originated to 14.1 percent but decreased their

market share of the term loans they originated to 8.8 percent.

These aggregate trends are consistent with the trends in the

average share of the credit that the lead bank retains on its

balance sheet. This share was equal to 32 percent for credit

lines in 1988 and 31 percent for term loans in the same

year. By 1999, these shares had declined to 17 percent and

16 percent, respectively. Then, in the first decade of the new

century, the average credit-line share retained by the lead

bank increased to 24 percent by 2006, whereas the average

share retained in term loans increased slightly but essentially

remained stable, at 17 percent, by the same year.

Since average retained shares are much higher than the

aggregate (market) shares, the data indicate that banks tend to

keep smaller shares of the larger credits that they originate.

Recall that the average retained share is a simple average of the

credit shares that banks keep on the balance sheet, while the

aggregate share is a weighted average of these shares, with the

weights defined by the size of the credits.

The disparity between the trends in lead banks’ market

shares of credit lines and term loans shows the effect of banks’

increasing syndication and securitization of term loans. These

trends, though suggestive of these effects, do not reflect the

whole story, since they account only for the role of lead banks

and exclude that of banks that participate in the loan syndicate

(syndicate-participant banks). We discuss this issue further in

a later section.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 27

Chart 4

Lead Banks’ Market Share of Term Loans

at Origination by Credit Purpose

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.4

0.2

0.3

0

0.1

Mergers and

acquisitions

Corporate purposes

Capital expenditures

Chart 5

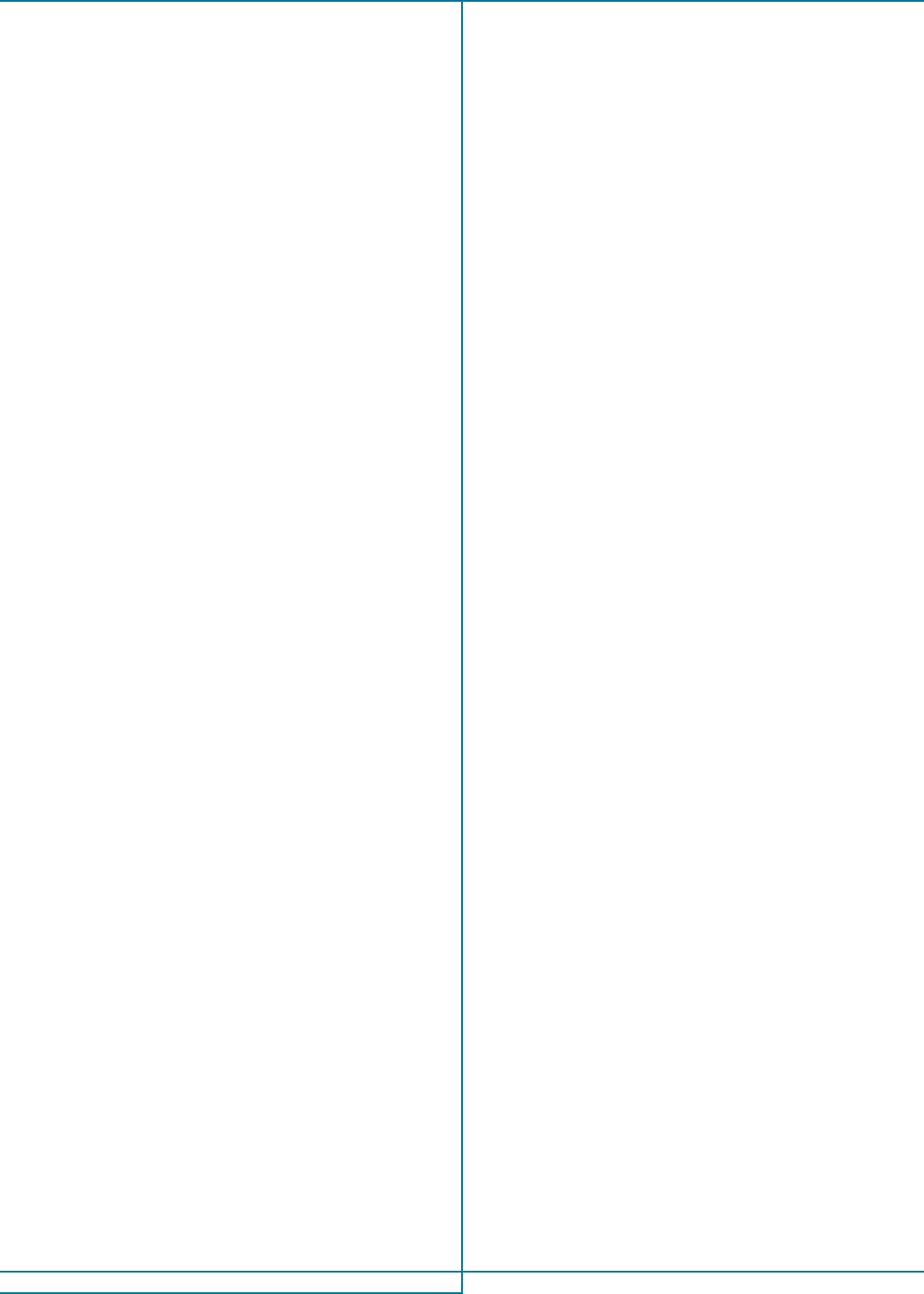

Lead Banks’ Market Share of Credits at Origination and Three Years Later

Market share

0.25

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

S

ource: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.30

0.15

0.20

0.10

0

0.05

0.25

0.30

0.15

0.20

0.10

0

0.05

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Credit Lines

Year 0

Year 3

Term Loans

Year 0

Year 3

Even though banks substituted the originate-to-distribute

model for the originate-to-hold model at a faster pace in their

term-loan business, they did not use the former uniformly

across all types of term loans. For instance, they varied their

retention rates depending on the purpose of the loan, as can

be seen in Chart 4. Over time, banks increasingly used the

originate-to-distribute model when they extended loans for

corporate purposes and in particular to fund mergers and

acquisitions, possibly because of the additional risk such

loans tend to carry. In contrast, they continued to use their

traditional originate-to-hold model when they extended

loans for capital expenditures.

3.2 Distribution after the Credit Origination

The decline in the share of credits that lead banks originate

did not occur only at the time of the credit origination but

continued throughout the life of the credit. To investigate this

effect, we began by selecting cohorts of credits originated each

year that we observed for at least three years. Next, we

computed the market share of the credits that the lead banks

retained at the time of origination and three years later. Both of

these shares are depicted in Chart 5. The left panel shows the

market shares for credit lines, while the right panel shows the

market shares for term loans. To allow us to observe all the

credits for three years, we end the chart with credits originated

in 2007. Recall that our sample ends in 2010.

A quick look at Chart 5 shows two important results. First,

in the years after credit-line origination, lead banks either did

not sell off additional portions of the credit lines or sold off a

very small (aggregate) share. This practice prevailed at the

beginning of our sample period in the late 1980s and continued

throughout the sample period, with the exception of the early-

to-mid-1990s when lead banks seemed to have sold off more

of the credit lines.

28 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

Second, as the term loans held by lead banks aged, the

banks increasingly reduced their aggregate exposure to them.

In the previous section, we documented that, over time, lead

banks retained at origination a smaller market share of the

term loans they originated. Chart 5 shows that this decline

continued even after the origination year. For example, of the

term loans that banks originated in 1988, they retained in

aggregate 21.4 percent at origination. Three years later, these

banks had, in aggregate, 18.7 percent of these term loans on

their balance sheet. In 2004, lead banks retained in aggregate

8.6 percent of the term loans they originated in that year.

Three years later, the banks’ aggregate exposure to the same

set of term loans had been reduced to 7.1 percent. In 2007, the

last year in our sample for which we conducted this exercise,

lead banks retained a market share of 6.7 percent of their term

loans at the time of origination. By 2010, they had lowered

their market share of these same term loans to 3.4 percent.

We obtain similar results when we track the individual share

of each credit that the lead bank retains on its balance sheet. For

credit lines, lead banks either decreased their average retained

shares very little or not at all. For example, of the credit lines

originated in 1988, on average banks retained 30.5 percent at

origination and 28.5 percent three years later. In 2004, lead

banks retained, on average, 21.6 percent at origination and

21.2 percent three years later. For term loans, however, lead

banks tended to cut back more of their credit exposure. Of the

term loans originated in 1988, banks retained an average of

35.2 percent at origination and 30.7 percent three years later.

In 2004, banks retained on average 19.2 percent at origination

and 18.0 percent three years later.

In sum, the results reported in this section show that over

the past two decades, banks largely continued to use the

traditional originate-to-hold model when they extended credit

lines to corporations but increasingly switched to the originate-

to-distribute model for term loans. This evidence suggests that

banks have a unique ability to provide liquidity to corporations

by extending credit lines to them. It also highlights the need

to reconsider the measures traditionally used to capture the

importance of banks as providers of credit to corporations.

As banks increasingly adopt the originate-to-distribute model,

conventional measures of bank lending activity, which rely on

the credit kept by banks on their balance sheets, will tend to

understate the role they play in the credit-origination process.

In the next section, we investigate which institutions are buying

the credits that banks originate.

4. Who Buys Bank Credit Lines

and Term Loans?

Given our finding that over time lead banks are retaining a

smaller and smaller portion of the credits they originate

(especially in the case of term loans), a natural question to ask

is, Who buys these credits? Answering this question—and, in

particular, finding out whether banks or other institutional

investors such as pension funds and hedge funds are buying

these credits—is important because these institutions have

quite different monitoring capabilities and incentives for

renegotiating existing credits. Answering this question also

helps us understand the growth of shadow banking in the past

decade and the links of these institutions to the banking sector.

4.1 The Role of Banks as Credit Acquirers

We start by investigating whether, as the lead banks have

lowered the share of credits they retain at origination, other

banks have increased the share of credit they hold as syndicate

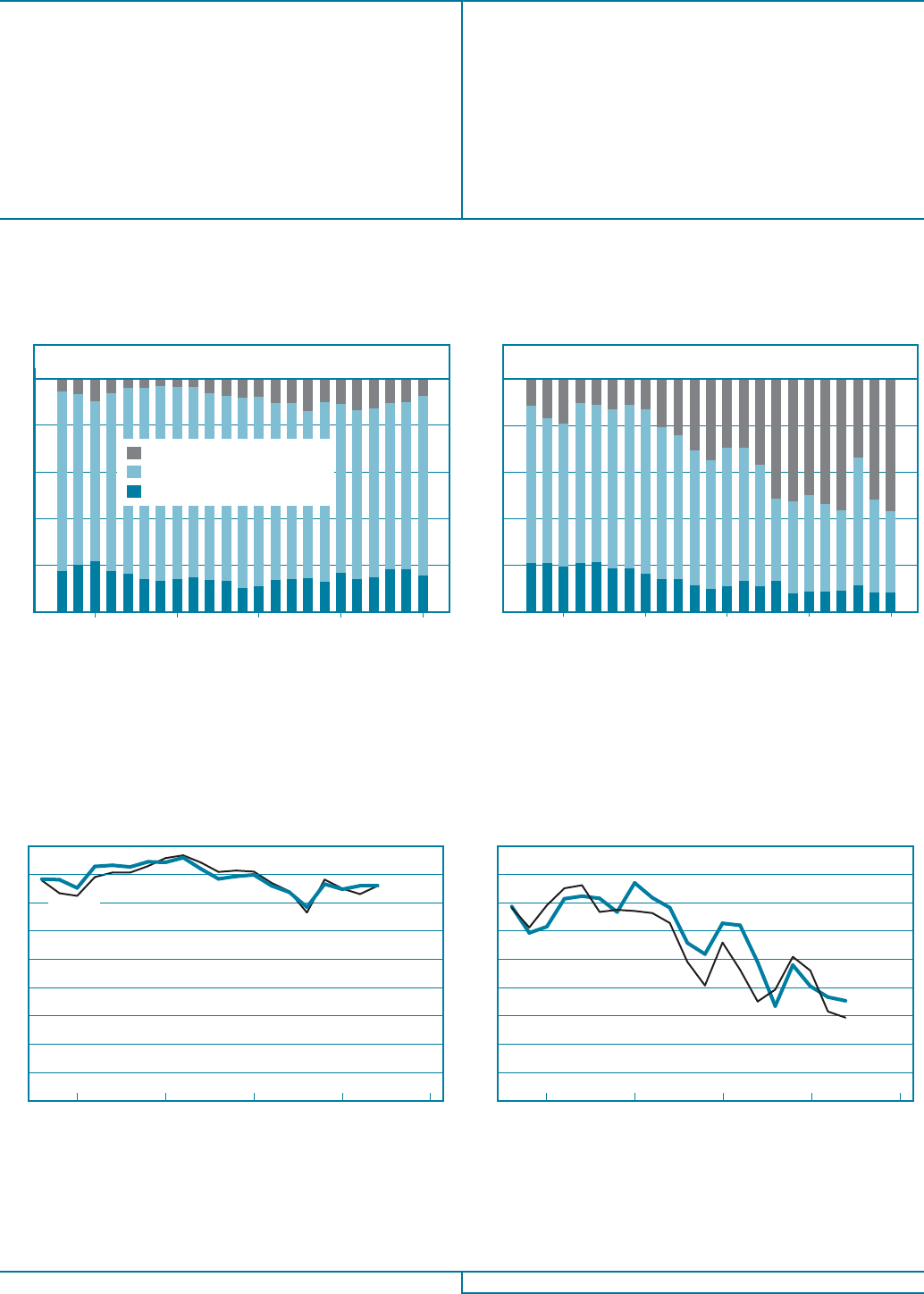

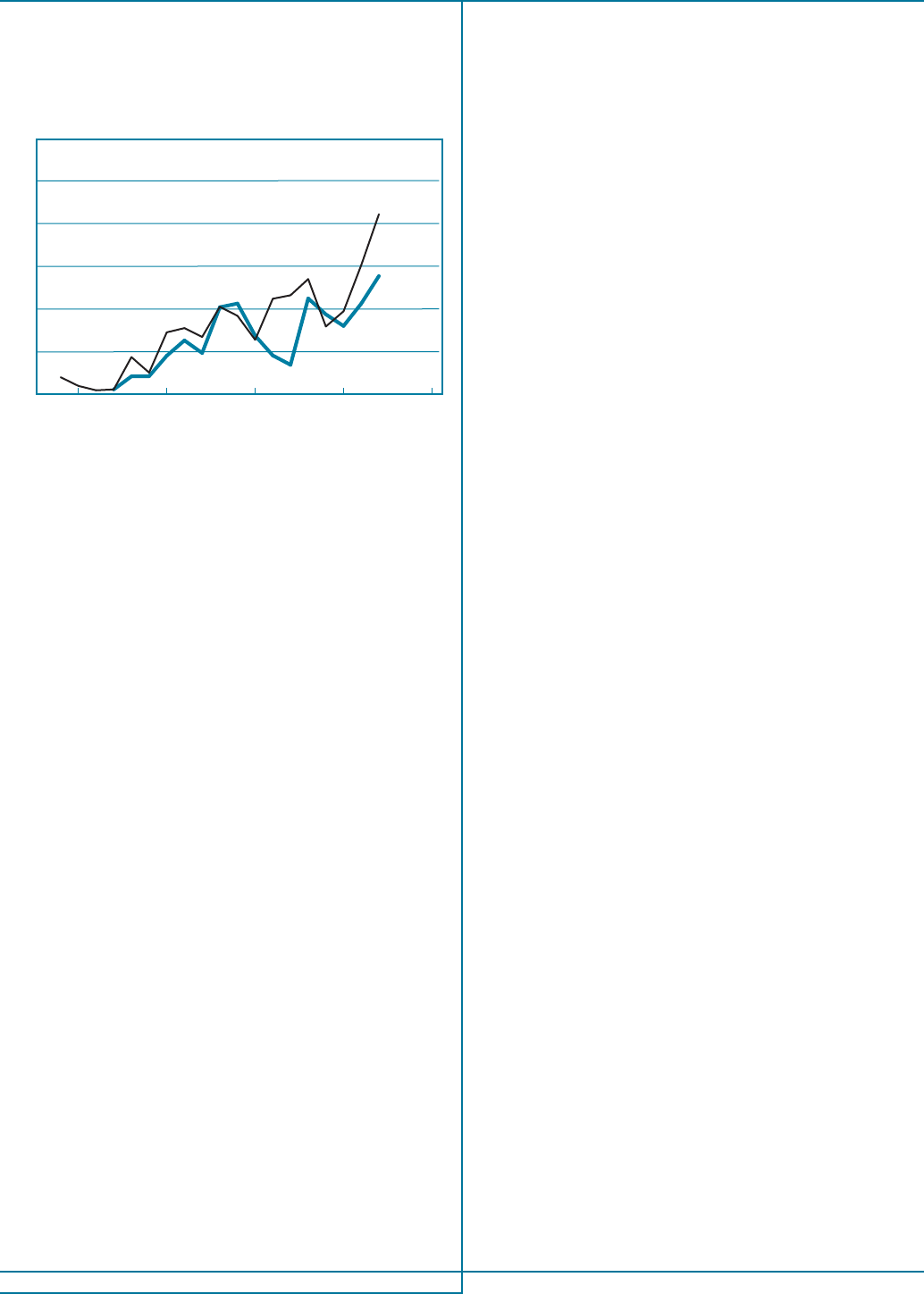

participants. The left panel of Chart 6 shows for the total credit

extended under credit lines each year, the portion that lead

banks retained, the portion acquired by banks that are

syndicate participants, and the portion acquired by the

remaining investors. The right panel of the chart reports the

same information for term loans.

As the chart shows, although the market share of credit

lines retained by lead banks decreased through the 1990s and

increased through the 2000s, the total market share held by all

banks (both lead and syndicate-participant banks) remains

fairly stable, at an average of 92 percent during the pre-crisis

sample period. In fact, when lead banks’ market share

decreased in the 1990s, the syndicate-participant banks’

market share increased, and that share increased more than

the lead banks’ share decreased. Similarly, from 2000 to 2010,

syndicate-participant banks’ market share decreased more

than the lead banks’ market share increased. In other words,

credit-line provision continues to be in essence a “bank

business.”

Term loans, however, present a different picture. As we can

see from the right panel of Chart 6, the decline in the lead

banks’ aggregate retained share was accompanied by an even

bigger decline in the share of the term loans acquired by other

banks.

15

15

The picture is fairly similar when we consider the average share held by

banks. For credit lines, the average share held by syndicate-participant banks

remained stable at approximately 10 percent throughout the time period.

By contrast, for term loans, the average share held by syndicate-participant

banks decreased from its peak of 14 percent in 1991 (11 percent in 1988) to

6.3 percent in 2006.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 29

Chart 6

Banks’ Retained Credits at Origination: Lead Banks versus Non-Lead Banks

Market share

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Credit Lines

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Term Loans

Lead banks

Syndicate-participant banks

Nonbanks

Chart 7

Syndicate-Participant Banks’ Market Share of Credits at Origination and Three Years Later

Market share

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.8

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

0.6

0.7

0.4

0.5

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.9

Credit Lines

0.8

0.6

0.7

0.4

0.5

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.9

Term Loans

Year 0

Year 3

Year 0

Year 3

Of the $47 billion in term loans originated in 1988, banks,

including lead banks and syndicate-participant banks, retained

on their balance sheet 88.6 percent of the amount of credit.

Of the $315 billion in term loans originated in 2007, banks

retained on their balance sheet 43.7 percent. Thus, banks (lead

banks and syndicate-participant banks) more than halved their

market share of term loans from 1988 to 2007.

These patterns remain when we consider how the market

share of bank investors changed over the life of the loan. As

Chart 7 shows, syndicate-participant banks did not sell off their

market share of credit lines during the lifetime of the loans but,

apart from short periods in the early 1990s and mid-2000s, they

did decrease their market share of term loans as the loans

matured. In fact, for term loans that we observe for at least

30 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

Chart 8

Nonbank Investors’ Market Share by Credit Type

Market share

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

S

ource: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.5

0.4

0.6

0.3

0.2

0

Credit Lines

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Term Loans

0.1

Insurance companies

Collateralized loan obligations

Brokers and investment banks

Investment management firms

Private equity firms

Pension funds

Finance companies

Other

Foreign nonbank organizations

three years, of the $17 billion of such loans originated in 1988,

banks (both lead and syndicate-participant banks) kept on

their balance sheets 90.2 percent in 1988 but only 86.9 percent

three years later. Similarly, of the $17 billion in term loans

issued in 2007, banks kept on their balance sheets 42.1 percent

at origination but only 32.8 percent three years later.

Thus, for credit lines, syndicate-participant banks tended to

offset the actions of the lead banks at origination, and they

tended to hold the credit lines to maturity (or at least for three

years). For term loans, in contrast, syndicate-participant banks,

like lead banks, have been decreasing the market share they

retain at origination and over the years after origination.

16

4.2 The Role of Nonbank Financial

Institutions

Given the decline in the portion of term loans retained in the

banking sector, the next question to ask is, Who are the

investors that have been increasing their presence in this

market? To address this question, we report in Chart 8 the

market shares at the time of credit origination in the credit-

line market (left panel) and the term-loan market (right

16

Interestingly, the average shares for syndicate-participant banks did not

change much over the life of the credit, for both credit lines and term loans.

With the exception of loans originated during the recessions of 1990 and 2001

(for which the average participant bank share decreased over the loans’

lifetime), on average, syndicate-participant banks retained the same share

at origination as three years later.

panel) of the main nonbank investors in these markets:

insurance companies, investment management firms, finance

companies, collateralized loan obligation managers, private

equity firms, brokers and investment banks, pension funds,

and foreign nonbank organizations.

17

Looking at the information on credit lines, we see that the

market share of nonbank investors in credit lines is very small,

less than 10 percent in each year. This finding was expected,

given our previous evidence that banks continue to play a

dominant role in the provision of liquidity to corporations

through credit lines. The nonbank entities that have the highest

market share are finance companies, pension plans, investment

managers, and “other.”

18

Finance companies first appear in

our credit-line data in 1992, when they held a market share

of 0.2 percent. They reached their peak market share in 2002

with 3.2 percent of all credit lines originated.

17

The different categories are identified in a variety of ways: by keyword;

by information from the National Information Center run by the Federal

Reserve System, which identifies banks, bank holding companies, foreign

banking organizations, finance companies, insurance companies, and so on;

by matching to the Moody’s Structured Finance Database, which allows us

to identify CLOs; and by matching to Capital IQ to identify investment

management firms and private equity firms. Investment management firms

are identified as hedge funds, mutual funds, or asset managers. Note that

institutions may shift across categories over time. For example, for most of

our sample, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley are identified as investment

banks. However, after they officially converted their status to BHCs in the

first quarter of 2009, they are classified as BHCs. Finally, note that for the

remaining analysis, we exclude nonbank entities that are part of banking

entities—for example, finance companies that are part of BHCs. (Including

them does not substantially change our analysis.)

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 31

Turning our attention to term loans, we see from the right

panel of Chart 8 that finance companies, CLOs, brokers, and

investment managers have been increasing their share in the

market for term loans and that nonbank investors—

particularly, investment managers and CLOs—play a much

bigger role in this market than in the credit-line market.

Investment managers first appear in our data in 1992, when

they acquired 2 percent of the term loans originated that year.

Similarly, CLOs first appear in our data in 1994, when they held

0.3 percent of the term loans originated in that year. By 2007,

these investors had acquired 13.6 percent and 15.5 percent,

respectively, of the term loans issued in that year. Again, note

that all of these numbers underestimate the true presence of

each category in the market since the “other” grouping

contains institutions that could not be accurately matched to

any of the categories from our sources; nonetheless, most of

these institutions probably do fall into one of these categories.

Finance companies first appear in the term-loan data in 1989,

when they acquired 0.03 percent of the term loans issued that

year; at their peak in 1998, they held 7.3 percent of the term

loans issued that year. Private equity firms currently represent

a small share of the market (0.8 percent in 2010), but they have

been steadily building their presence in this market, from

0.4 percent in 1996 to 3 percent in 2007. In contrast, insurance

companies continue to play a minor role: the share of the term

loans held by insurance companies increased from 0.2 percent

in 1988 to 1.0 percent in 2007.

4.3 Nonbank Investors’ Shares

after Loan Origination

We documented earlier that both lead banks and syndicate-

participant banks continue to reduce the share of their term

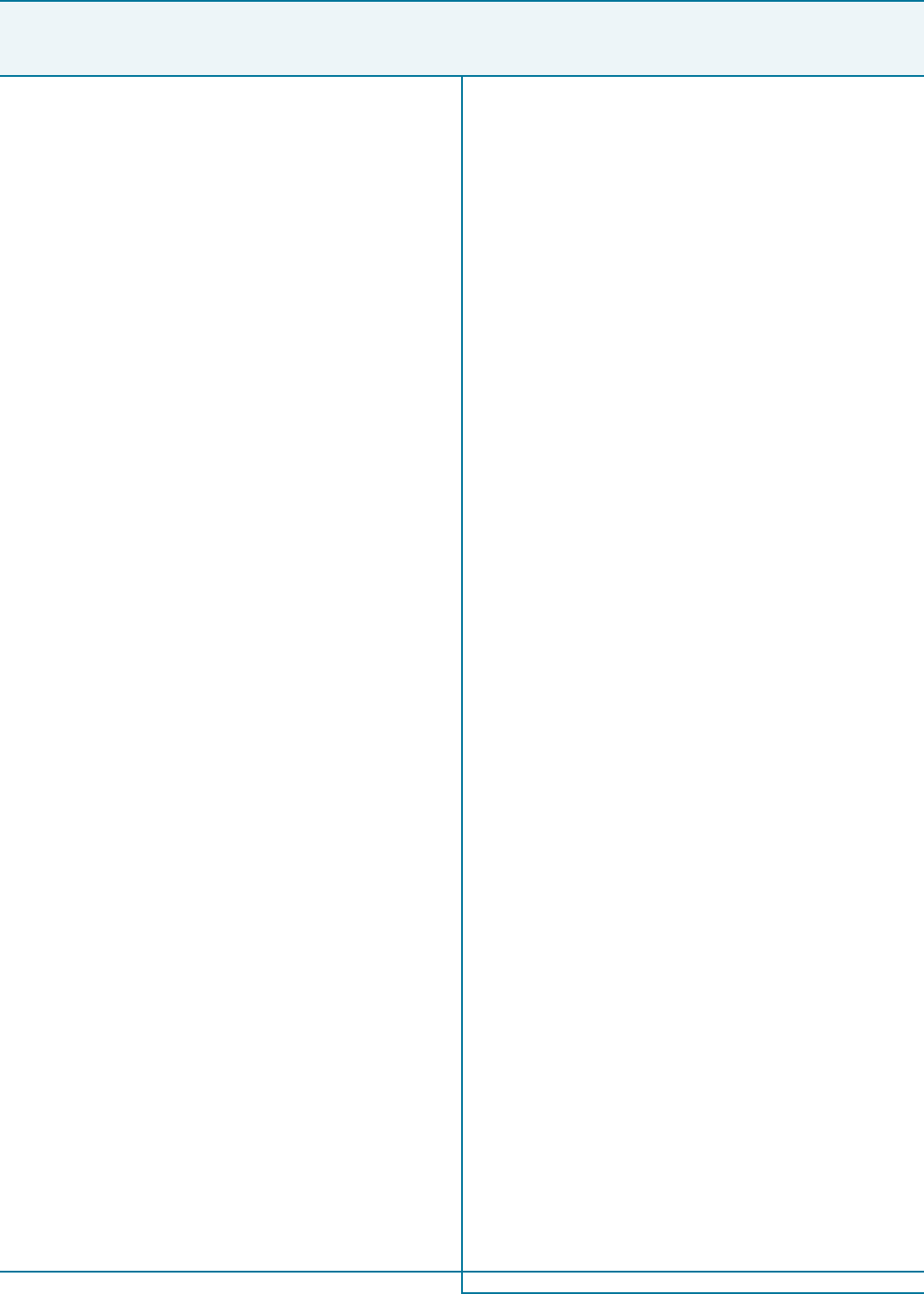

loans in the years following origination. In Charts 9 through

11, we examine the market shares of the top three nonbank

investors in the syndicated loan market at the time of the credit

origination and three years later. Because these nonbank

investors invest mainly in term loans, we limit our analysis

to the term-loan market.

Finance companies kept their share of the term-loan market

more or less constant over the past decade. In contrast, CLOs

and investment managers have been increasing their market

18

The majority of the institutions in the “other” category were not clearly

identified by our sources as belonging to one of the categories discussed above.

Because much of the identification was done through name matching,

institutions for which the quality of the match was in question were also placed

in the “other” category. Finally, the category also contains a very small number

of Article XII New York investment companies, data processing servicers,

individuals, and foundations.

share of the term-loan business. These investors have been

buying larger portions of the credits at the time of their

origination, and they continue to increase such investments

in the years after origination. From 2000 to 2007, on average,

CLOs acquired 12.6 percent of the term loans originated in

each year, while investment managers acquired on average

Chart 10

Role of Investment Managers

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.30

0.20

0.25

0

0.05

Year 0

Year 3

0.10

0.15

Chart 9

Role of Finance Companies

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.30

0.20

0.25

0

0.05

Year 0

Year 3

0.10

0.15

32 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

Chart 11

Role of Collateralized Loan Obligations

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Source: Shared National Credit database, produced jointly by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Market share

0.30

0.20

0.25

0

0.05

Year 0

Year 3

0.10

0.15

8.7 percent of this market. Three years later, such institutions

held 18.2 percent and 12.9 percent of these loans, respectively.

This evidence shows that over the past two decades, as banks

have increasingly opted to retain on their balance sheet a

smaller portion of the term loans they originated, they have

been fueling the growth of nonbank institutions, in particular

CLOs and investment managers.

5. Final Remarks

Our analysis of banks’ role in financial intermediation reveals

that beginning in the early 1990s, lead banks increasingly used

the originate-to-distribute model in their corporate lending

business. This increase, however, was largely limited to term

loans. In general, banks continued to rely on the traditional

originate-to-hold model in the credit-line business. Further,

we find that more and more lead banks “distributed” their

term loans by selling larger portions of them, not only at

the time of the loan origination but also in the years after

origination.

Our investigation into the investors that bought the bank

loans shows that traditional institutional investors and, in

particular, new loan investors—including investment managers

and CLOs—began taking over more of the credit business.

Our findings have several important implications for the

theme of this volume. They show that in evaluating the

importance of banks in financial intermediation, analysts must

use measures of the credit that banks originate, as opposed to

measures of the credit they retain on their balance sheets.

Indeed, our findings confirm that measures of the importance

of banks that rely on the credit held by banks on their balance

sheets will increasingly understate the essential role that banks

play in financial intermediation. Our findings also show that

banks have been an important contributor to the so-called

shadow banking system.

19

For example, in 1993, of the

$22.7 billion in term loans originated, banks sold $2.2 billion to

the shadow banking system. By comparison, in 2007, of the

$315 billion in term loans originated, they sold $125 billion to

the shadow banking system. In about two decades, the annual

volume of term loans that banks supplied to nonaffiliated

shadow-banking institutions increased by $123 billion.

Lastly, our findings suggest some interesting questions

for future research. Does the increasing presence of nonbank

financial institutions in loan syndicates affect lending terms or

hinder borrowers’ ability to renegotiate their credits? Does the

decline in a lead bank’s retained share of the credits it originates

affect the nature of its relationship with borrowers? What are

the implications of the decline in a bank’s retained share for its

incentives to assess the creditworthiness of loan applicants or

to track the viability of loans? Researchers have been using the

share of a credit held by the lead bank at the time of origination

as a proxy for the bank’s monitoring incentives. As our

evidence shows, however, this share may be a biased proxy

for the bank’s exposure during the life of a loan. It would be

interesting to investigate the implications of the decline in the

bank’s credit share for its monitoring incentives during the life

of the credit.

19

For these computations, “shadow banking institutions” are defined as CLOs,

brokers and investment banks, investment managers, private equity firms,

finance companies, and foreign nonbank institutions.

References

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 33

Altman, E. I., A. Gande, and A. Saunders. 2004. “Informational

Efficiency of Loans versus Bonds: Evidence from Secondary

Market Prices.” New York University Working Paper

no. S-FI-04-02, February. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/

abstract=1297736.

Bharath, S. T., S. Dahiya, A. Saunders, and A. Srinivasan. 2009.

“Lending Relationships and Loan Contract Terms.” Working

paper, New York University Stern School of Business.

Bord, V. M., and J. A. C. Santos. 2010. “Did the Rise of CLOs Lead

to Riskier Lending?” Unpublished paper, Federal Reserve Bank

of New York.

———. 2011. “Banks’ Liquidity and the Cost of Liquidity to

Corporations.” Unpublished paper, Federal Reserve Bank

of New York, September.

Cetorelli, N., and S. Peristiani. 2012. “The Role of Banks in Asset

Securitization.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic

Policy Review 18, no. 2 (July): 47-63.

Dennis, S. A., and D. J. Mullineaux. 2000. “Syndicated Loans.”

Journal of Financial Intermediation 9, no. 4 (October):

404-26.

Diamond, D. W. 1984. “Financial Intermediation and Delegated

Monitoring.” Review of Economic Studies 51, no. 3 (July):

393-414.

Focarelli, D., A. F. Pozzolo, and L. Casolaro. 2008. “The Pricing Effect

of Certification on Bank Loans: Evidence from the Syndicated

Credit Market.” Journal of Monetary Economics 55, no. 2

(March): 335-49.

Gatev, E., and P. Strahan. 2006. “Banks’ Advantage in Hedging

Liquidity Risk: Theory and Evidence from the Commercial Paper

Market.” Journal of Finance 61, no. 2 (April): 867-92.

Gatev, E., T. Schuermann, and P. E. Strahan. 2009. “Managing Bank

Liquidity Risk: How Deposit-Loan Synergies Vary with Market

Conditions.” Review of Financial Studies 22, no. 3 (March):

995-1020.

Gorton, G. B., and J. G. Haubrich. 1990. “The Loan Sales Market.”

Research in Financial Services 2: 85-135.

Gorton, G. B., and G. G. Pennacchi. 1995. “Banks and Loan Sales:

Marketing Nonmarketable Assets.” Journal of Monetary

Economics 35, no. 3 (June): 389-411.

Hale, G. B., and J. A. C. Santos. 2009. “Do Banks Price Their

Informational Monopoly?” Journal of Financial

Economics 93, no. 2 (August): 185-206.

———. 2010. “Do Banks Propagate Debt Market Shocks?”

Unpublished paper, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, February.

Holmström, B. R., and J. Tirole. 1993. “Market Liquidity and

Performance Monitoring.” Journal of Political Economy 101,

no. 4 (August): 678-709.

———. 1998. “Private and Public Supply of Liquidity.” Journal

of Political Economy 106, no. 1 (February): 1-40.

Hubbard, R. G., K. N. Kuttner, and D. N. Palia. 2002. “Are There Bank

Effects in Borrowers’ Costs of Funds? Evidence from a Matched

Sample of Borrowers and Banks.” Journal of Business 75, no. 4

(October): 559-81.

Hugh, T., and Z. Wang. 2004. “The Integration of Bank Syndicated

Loan and Junk Bond Markets.”

Journal of Banking and

Finance 28, no. 2 (February): 299-329.

Ivashina, V. 2009. “Asymmetric Information Effects on Loan

Spreads.” Journal of Financial Economics 92, no. 2 (May):

300-19.

Kashyap, A. K., R. G. Rajan, and J. C. Stein. 2002. “Banks as Liquidity

Providers: An Explanation for the Coexistence of Lending and

Deposit-Taking.” Journal of Finance 57, no. 1 (February):

33-73.

Mian, A., and J. A. C. Santos. 2011. “Liquidity Risk and Maturity

Management over the Credit Cycle.” Unpublished paper, Federal

Reserve Bank of New York.

Paligorova, T., and J. A. C. Santos. 2011. “When Is It Less Costly for

Risky Firms to Borrow? Evidence from the Bank Risk-Taking

Channel of Monetary Policy.” Unpublished paper, Federal Reserve

Bank of New York.

References (Continued)

34 The Rise of the Originate-to-Distribute Model

Pennacchi, G. G. 1988. “Loan Sales and the Cost of Bank Capital.”

Journal of Finance 43, no. 2 (March-April): 375-96.

Pozsar, Z., T. Adrian, A. Ashcraft, and H. Boesky. 2010. “Shadow

Banking.” Federal Reverse Bank of New York Staff Reports,

no. 458, July.

Ramakrishnan, R. T. S., and A. V. Thakor. 1984. “Information

Reliability and a Theory of Financial Intermediation.” Review

of Economic Studies 51, no. 3 (July): 415-32.

Roberts, M., and A. Sufi. 2009. “Renegotiation of Financial Contracts:

Evidence from Private Credit Agreements.” Journal of

Financial Economics 93, no. 2 (August): 159-84.

Santos, J. A. C. 2011. “Bank Loan Pricing following the Subprime

Crisis.” Review of Financial Studies 24, no. 6 (June): 1916-43.

———. 2012. “Banks’ Liquidity Insurance Provision to Firms and

Depositors and the Risk of Cìoncurrent Runs on Their Assets

and Liabilities.” Unpublished paper, Federal Reserve Bank

of New York.

Santos, J. A. C., and A. Winton. 2008. “Bank Loans, Bonds, and

Informational Monopolies across the Business Cycle.” Journal

of Finance 63, no. 3 (June): 1315-59.

———. 2010. “Bank Capital, Borrower Power, and Loan Rates.”

Unpublished paper, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Sufi, A. 2007. “Information Asymmetry and Financing Arrangements:

Evidence from Syndicated Loans.” Journal of Finance 62, no. 2

(April): 629-68.

Yago, G., and D. McCarthy. 2004. “The U.S. Leveraged Loan Market:

A Primer.” Milken Institute, October.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

or the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York provides no warranty, express or implied, as to the

accuracy, timeliness, completeness, merchantability, or fitness for any particular purpose of any information contained in

documents produced and provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in any form or manner whatsoever.