Human Rights:

A Brief Introduction

Stephen P. Marks

Harvard University

© Harvard University 2016

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

1

Human Rights: A Brief Introduction

Stephen P. Marks

Harvard University

I: Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1!

II. Human rights in ethics, law and social activism ......................................................................... 1!

A. Human rights as ethical concerns ........................................................................................... 2!

B. Human rights as legal rights (positive law tradition) .............................................................. 3!

C. Human rights as social claims ................................................................................................ 4!

III: Historical milestones ................................................................................................................. 5!

IV: Tensions and controversies about human rights today ............................................................. 7!

A. Why do sovereign states accept human rights obligations? ................................................... 7!

B. How do we know which rights are recognized as human rights? ........................................... 8!

Table 1: List of human rights .............................................................................................. 9!

C. Are human rights the same for everyone? ............................................................................ 11!

D. How are human rights put into practice? .............................................................................. 13!

1. The norm-creating process ................................................................................................ 13!

Table 2: Norm-creating process ........................................................................................ 13!

2. The norm-enforcing process .............................................................................................. 14!

3. Continuing and new challenges to human rights realization ............................................ 16!

Table 3: Means and methods of human rights implementation ........................................ 17!

V: Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 18!

Selected bibliography .................................................................................................................... 19!

Selected websites ........................................................................................................................... 19!

Universal Declaration of Human Rights ....................................................................................... 21!

I: Introduction

Human rights constitute a set of norms

governing the treatment of individuals and

groups by states and non-state actors on the

basis of ethical principles regarding what

society considers fundamental to a decent

life. These norms are incorporated into

national and international legal systems,

which specify mechanisms and procedures

to hold the duty-bearers accountable and

provide redress for alleged victims of human

rights violations.

After a brief discussion of the use of

human rights in ethical, legal and advocacy

discourse and some historical background of

the concept of human rights, this essay will

examine the tensions between human rights

and state sovereignty, the challenges to the

universality of human rights, the

enumeration of rights recognized by the

international community, and the means

available to translate the high aspirations of

human rights into practice.

II. Human rights in ethics, law and

social activism

There are numerous theoretical debates

surrounding the origins, scope and

significance of human rights in political

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

2

science, moral philosophy, and

jurisprudence. Roughly speaking, invoking

the term “human rights” (which is often

referred to as “human rights discourse” or

“human rights talk”) is based on moral

reasoning (ethical discourse), socially

sanctioned norms (legal/political discourse)

or social mobilization (advocacy discourse).

These three types of discourse are by no

means alternative or sequential but are all

used in different contexts, depending on

who is invoking human rights discourse, to

whom they are addressing their claims, and

what they expect to gain by doing so. The

three types of discourse are inter-related in

the sense that public reasoning based on

ethical arguments and social mobilization

based on advocacy agendas influence legal

norms, processes and institutions and thus

all three modes of discourse contribute to

human rights becoming part of social reality.

A. Human rights as ethical concerns

Human rights have in common an

ethical concern for just treatment, built on

empathy or altruism in human behavior and

concepts of justice in philosophy. The

philosopher and economist, Amartya Sen,

considers that “Human rights can be seen as

primarily ethical demands… Like other

ethical claims that demand acceptance, there

is an implicit presumption in making

pronouncements on human rights that the

underlying ethical claims will survive open

and informed scrutiny.”

1

In moral

reasoning, the expression “human rights” is

often not distinguished from the more

general concept of “rights,” although in law

a “right” refers to any entitlement protected

by law, the moral validity or legitimacy of

which may be separate from its legal status

as an entitlement. The moral basis of a right

1

Amartya Sen, “Elements of a Theory of Human

Rights,” Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 32, No. 4

(2004), p. 320.

can draw on concepts such as natural law,

social contract, justice as fairness,

consequentialism and other theories of

justice. In all these philosophical traditions,

a right is conceived as an entitlement of

individuals, either by virtue of being human

or because they are members of a political

community (citizens). In law, however, a

right is any legally protected interest,

whatever the social consequence of the

enforcement of the right on the wellbeing of

persons other than the right-holder (e.g., the

property right of a landlord to evict a tenant,

the right of a business to earn profits). To

avoid confusion, it is helpful to use the term

“human right” or its equivalent

(“fundamental right,” “basic freedom,”

“constitutional right”) to refer to a higher-

order right, authoritatively defined and

carrying the expectation that it has a

peremptory character and thus prevails over

other (ordinary) rights and reflects the

essential values of the society adopting it.

Ethical and religious precepts determine

what one is willing to accept as properly a

human right. Such precepts are typically

invoked in the debates over current issues

such as abortion, same-sex marriage, the

death penalty, migration, much as they were

around slavery and inequality based on

class, gender or ethnicity in the past.

Enlightenment philosophers derived the

centrality of the individual from their

theories of the state of nature. Social

contractarians, especially Jean-Jacques

Rousseau, predicated the authority of the

state on its capacity to achieve the optimum

enjoyment of natural rights, that is, of rights

inherent in each individual irrespective of

birth or status. He wrote in Essay on the

Origin on Inequality Among Men that “it is

plainly contrary to the law of nature…that

the privileged few should gorge themselves

with superfluities, while the starving

multitude are in want of the bare necessities

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

3

of life.”

2

Equally important was the concept

of the universalized individual (“the rights

of Man”), reflected in the political thinking

of Immanuel Kant, John Locke, Thomas

Paine and the authors of the American

Declaration of Independence (1776) and the

French Declaration of the Rights of Man and

the Citizen (1789). The Enlightenment

represents for the West both the affirmation

of the scientific method with the related

faith of human progress and the formulation

of the human rights, which define the

freedom and equality on which the

legitimacy of modern governments have

henceforth been judged. Karl Marx and

much of socialist thinking questioned the

“bourgeois” character of a limited

interpretation of individual human rights and

stressed community interests and egalitarian

values.

The ethical basis of human rights has

been defined using concepts such as human

flourishing, dignity, duties to family and

society, natural rights, individual freedom,

and social justice against exploitation based

on sex, class or caste. All of these moral

arguments for human rights are part of

ethical discourse. The tension between

political liberalism and democratic

egalitarianism, between Locke and

Rousseau, between liberty and equality,

between civil and political rights and

economic, social and cultural rights, have

been part of the philosophical and political

ambiguity of human rights since the

beginning of the modern era.

Whether human rights discourse is

essentially ethical and philosophical or

rather essentially legal and political is a

matter of dispute. Sen writes, “Even though

human rights can, and often do, inspire

legislation, this is a further fact, rather than

2

D.G.H. Cole translation, p. 117.

an constitutive characteristic of human

rights”

3

, implying an inherent value of the

concept of human rights, independent of

what is established in law. Legal positivists

would disagree and consider law to be

constitutive rather than declarative of human

rights.

B. Human rights as legal rights (positive

law tradition)

“Legal positivists” regard human rights

as resulting from a formal norm-creating

process, by which we mean an authoritative

formulation of the rules by which a society

(national or international) is governed.

While “natural rights” derive from natural

order or divine origin, and are inalienable,

immutable, and absolute, rights based on

“positive law” are recognized through a

political and legal process that results in a

declaration, law, treaty, or other normative

instrument. These may vary over time and

be subject to derogations or limitations

designed to optimize respect for human

rights rather than impose an absolute

standard. They become part of the social

order when an authoritative body proclaims

them, and they attain a higher degree of

universality based on the participation of

virtually every nation in the norm-creating

process, a process that is law-based but that

reflects compromise and historical shifts.

Think of the moral and legal acceptability of

slavery, torture, or sexual and racial

discrimination over most of human history.

The product of what has survived “open and

informed scrutiny” (Sen’s expression) is

thus often found not in journals and

seminars on ethics and normative theory but

rather at the end of the political or legislative

process leading to the adoption of laws and

treaties relating to human rights, such as the

relatively recent abolition of slavery, torture

3

Sen, supra, note 1, p. 319

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

4

and discrimination based on race or sex.

The “International Bill of Human

Rights” (consisting of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights [UDHR] of

1948, and two legally-binding treaties

opened for signature in 1966, namely, the

International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights and the International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights),

along with the other human rights treaties of

the United Nations (UN) and of regional

organizations, constitute the primary sources

and reference points for what properly

belongs in the category of human rights.

These legally recognized human rights are

discussed below in Part IV.B.

C. Human rights as social claims

Before they are written into legal texts,

human rights often emerge from claims of

people suffering injustice and thus are based

on moral sentiment, culturally determined

by contextualized moral and religious belief

systems. Revolt against tyranny is an ancient

tradition. A modern precursor of social

mobilization for human rights at the national

level was the response to the unjust

condemnation of Captain Dreyfus in 1894 as

a spy for the Germans, which led Emile Zola

to proclaim in his famous “J’Accuse…!”, an

impassioned call to action that led to the

creation of the Ligue française des droits de

l’homme in 1897, and numerous similar

leagues, which became federated in 1922 into

the International Federation of Leagues for

the Rights of Man (now the International

Federation for Human Rights), which

spawned its counterpart in the US in 1942, the

International League for the Rights of Man,

now functioning in New York as the

International League for Human Rights.

Amnesty International (founded in 1961), the

Moscow Human Rights Committee (founded

in 1970), and Helsinki Watch (founded in

1978 and expanded into Human Rights Watch

in 1988) were among the more effective non-

governmental organizations (NGOs). Latin

America, Africa and Asia saw the creation of

an extraordinary array of human rights groups

in the 1980s and 1990s, which have

proliferated after the end of the Cold War.

These NGOs emerged as social

movements catalyzed by outrage at the

mistreatment of prisoners, the exploitation of

workers, the exclusion of women, children,

persons with disabilities, or as part of

struggles against slavery, the caste system,

colonialism, apartheid, or predatory

globalization. Such movements for social

change often invoke human rights as the basis

of their advocacy. If the prevailing theories of

moral philosophy or the extant codes of

human rights do not address their concerns,

their action is directed at changing the theory

and the legal formulations. NGOs not only

contributed to the drafting of the UDHR but

also in bringing down Apartheid,

4

transforming the political and legal

configuration of East-Central Europe

5

and

restoring democracy in Latin America.

6

New

norms emerged as a result of such social

mobilization during the second half of the

twentieth century regarding self-

determination of peoples, prevention and

punishment of torture, protection of

vulnerable groups and, more recently, equal

treatment of sexual minorities and protection

of migrants.

The appeal to human rights in this

advocacy discourse is no less legitimate than

the legal and philosophical modes of

discourse and is often the inspiration for the

latter. Quoting Sen again, “The invoking of

4

William Korey, NGOs and the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights: A Curious Grapevine,

pp. 7-8.

5

Id., pp. 95-116.

6

Id., pp. 229-247.

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

5

human rights tends to come mostly from

those who are concerned with changing the

world rather than interpreting it… The

colossal appeal of the idea of human rights

[has provided comfort to those suffering]

intense oppression or great misery, without

having to wait for the theoretical air to

clear.”

7

Former British diplomat and law

professor Philip Allott expressed the

transformative potential of human rights

when he found that there was, “room for

optimism on two grounds. (1) The idea of

human rights having been thought, it cannot

be unthought. It will not be replaced, unless

by some idea which contains and surpasses

it. (2) There are tenacious individuals and

non-statal societies whose activity on behalf

of the idea of human rights is not part of

international relations but is part of a new

process of international reality-forming.”

8

He adds, “The idea of human rights should

intimidate governments or it is worth

nothing. If the idea of human rights

reassures governments, it is worse than

nothing.”

9

In sum, the force of social

movements drawing inspiration from human

rights not only enriches the concept of

human rights but also contributes to altering

international society.

III: Historical milestones

The historical context of human rights

can be seen from a wide range of

perspectives. At the risk of

oversimplification, I will mention four

approaches to the history of human rights.

The first approach traces the deeper

7

Sen, supra, note 1, p. 317.

8

Philip Allott, Eunomia: New Order for a New

World, Oxford University Press, 1990, p. 287.

9

Id.

origins to ancient religious and

philosophical concepts of compassion,

charity, justice, individual worth, and

respect for all life found in Hinduism,

Judaism, Buddhism, Confucianism,

Christianity and Islam. Precursors of human

rights declarations are found in the ancient

codes of Hammurabi in Babylon (about

1772 BCE), the Charter of Cyrus the Great

in Persia (about 535 BCE), edicts of Ashoka

in India (about 250 BCE), and rules and

traditions of pre-colonial Africa and pre-

Columbian America.

10

Others trace modern human rights to the

emergence of natural law theories in Ancient

Greece and Rome and Christian theology of

the Middle Ages, culminating in the

rebellions in the 17

th

and 18

th

century

Europe, the philosophers of the

Enlightenment and the Declarations that

launched the French and American

revolutions, combined with the 19

th

century

abolitionist, workers’ rights and women’s

suffrage movements.

11

A third trend is to trace human rights to

their enthronement in the United Nations

Charter of 1945, in reaction to the Holocaust

and drawing on President Roosevelt’s Four

Freedoms and the impact of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 on

subsequent national constitutions and

foreign policy and international treaties and

10

Micheline Ishay, The History of Human Rights:

From Ancient Times to the Globalization Era, With a

New Preface, New York: Norton and Co., 2008. See

also Micheline Ishay (ed.), The Human Rights

Reader: Major Political Essays, Speeches, and

Documents from Ancient Times to the Present,

Second Edition, New York: Routledge, 2007.

Another interesting compilation may be found in

Jeanne Hersch (ed.), Birthright of Man, UNESCO,

1969. The French edition was published in 1968. A

second edition was published in 1985.

11

Lynn Hunt, Inventing Human Rights: A History,

New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

6

declarations.

12

A fourth view is the very recent

revisionist history that considers human

rights as peripheral in the aftermath of

World War II and only significant as a

utopian ideal and movement beginning in

the 1970s as an alternative to the prevailing

ideological climate.

13

Much scholarship, especially in Europe

and North America, dates modern human

rights theory and practice from the

Enlightenment and the transformative

influence of the French and American

Revolutions of the 18

th

century and

liberation of subjugated people from slavery

and colonial domination in the 19

th

and 20

th

centuries. Lynn Hunt, in an essay on “The

Revolutionary Origins of Human Rights,”

affirms that:

Most debates about rights originated in

the eighteenth century, and nowhere

were discussions of them more

explicit, more divisive, or more

influential than in revolutionary

France in the 1790s. The answers

given then to most fundamental

questions about rights remained

relevant throughout the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries. The framers of

the UN declaration of 1948 closely

followed the model established by the

French Declaration of the Rights of

Man and Citizen of 1789, while

substituting “human” for the more

12

Paul Gordon Lauren, The Evolution of

International Human Rights: Visions Seen,

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998;

Hersch Lauterpacht, International Law and Human

Rights, with an introduction by Isidore Silver. New

York: Garland, 1950 (reprint 1973).

13

Samuel Moyn, The Last Utopia: Human Rights in

History, Cambridge MA: Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press, 2012; Aryeh Neier, The

International Human Rights Movement: A History,

Princeton, NY,: Princeton University Press 2012.

ambiguous “Man” throughout.

14

Commenting on the French

Revolution’s break with the past, Jürgen

Habermas wrote that this “revolutionary

consciousness gave birth to a new mentality,

which was shaped by a new time

consciousness, a new concept of political

practice, and a new notion of

legitimization.”

15

Although it took more

than a century after the French Revolution

for this new mentality to include women and

people subjected to slavery, the awareness

that the “rights of man” should extend to all

human beings was forcefully argued in the

same period by Mary Wollstonecreaft’s A

Vindication of the Rights of Woman

16

and by

the Society for the Abolition of the Slave

Trade, founded in 1783. The valuation of

every individual through natural rights was a

break with the earlier determination of rights

and duties on the basis of hierarchy and

status. Concepts of human progress and

human rights advanced in the 19th century,

when capitalism and the industrial

revolution transformed the global economy

and generated immense wealth at the

expense of colonized peoples and oppressed

workers. Human rights advanced but mainly

for propertied males in Western societies.

Since the 19

th

century, the human rights of

former colonialized peoples, women,

14

Lynn Hunt, ed., The French Revolution and Human

Rights. A Brief Documentary History, Boston, New

York: Bedord Boods of St. Martin’s Press, 1996, p. 3.

See also Stephen P. Marks, “From the ‘Single

Confused Page’ to the ‘Decalogue for Six Billion

Persons’: The Roots of the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights in the French Revolution,” Human

Rights Quarterly, vol. 20, No. 3, August 1998, pp.

459-514.

15

Jürgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms. A

Contribution to a Discourse Theory of Law and

Democracy, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1996,

p. 467.

16

Mary Wollstonecreaft, A Vindication of the Rights of

Woman, (1792)

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

7

excluded minorities, and workers has

advanced but the gap remains between the

theory of human rights belonging to all,

regardless of race, sex, language, religion,

political or other opinion, national or social

origin, caste, property, birth or other status,

and the reality of inequality and

discrimination.

The Second World War was the

defining event for the internationalization of

human rights. In 1940, H.G. Wells wrote

The Rights of Man or What are We Fighting

For?; Roosevelt announced the “four

freedoms” (freedoms of speech and worship

and freedoms from want and fear) in his

1941 State of the Union address; the UN

Charter established in 1945 an obligation of

all members to respect and observe human

rights and created a permanent commission

to promote their realization; the trial of Nazi

doctors defined principles of bioethics that

were codified in the Nuremberg Code in

1946; and the Nuremberg Trials, in 1945–

46, of 24 of the most important captured

leaders of Nazi Germany, established

individual criminal responsibility for mass

human rights violations. Each of these

events connected with World War II has had

major repercussions for human rights today.

In the War’s immediate aftermath, bedrock

human rights texts were adopted: the

Genocide Convention and the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the

Geneva Conventions in 1949 on the

protection of victims of armed conflict,

followed in 1966 by the International

Covenants on Human Rights and scores of

UN and regional human rights texts on

issues such as torture, the rights of the child,

minorities, discrimination against women,

and disability rights, along with the creation

of investigative and accountability

procedures at the intergovernmental level.

Individual criminal responsibility for mass

violations of human rights re-emerged—

after the hiatus of the Cold War—in the ad

hoc tribunals on Rwanda and former

Yugoslavia and finally in the International

Criminal Court.

IV: Tensions and controversies

about human rights today

To understand how human rights are

part of the global agenda, we need to ask (A)

why states even accept the idea of human

rights obligations when they are supposed to

be sovereign and therefore do what they

want within their territory. Then we will

explore (B) what is the current list of human

rights generally accepted, before asking (C)

whether they correspond to the basic values

of all societies or are imposed from the

outside for ideological reasons. Finally, we

will examine (D) how they are transformed

from word to deed, from aspiration to

practice.

A. Why do sovereign states accept human

rights obligations?

The principle of state sovereignty

means that neither another state nor an

international organization can intervene in a

state’s action to adopt, interpret and enforce

its laws within its jurisdiction. Does this

principle of non-intervention in domestic

affairs of states mean that they are free to

violate human rights? Along with the

principle of non-intervention, upon joining

the United Nations, states have pledged

themselves “to take joint and separate action

in co-operation with the Organization for the

achievement of the purposes set forth in

Article 55,”

17

which include the promotion

of “universal respect for, and observance of,

human rights and fundamental freedoms for

all without distinction as to race, sex,

language, or religion.”

18

17

Article 56 of the UN Charter.

18

Article 55 of the UN Charter. Article 1(3) of the

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

8

State sovereignty is therefore balanced

with legitimate concern of the international

community about human rights in all

countries. How that balance is interpreted

varies according to theories of international

relations. For those of the realist school (a

theory that focuses on governments as

autonomous and sovereign actors in

international affairs, pursuing their national

interests through the projection of economic,

military and political power, without

constraints of any superior authority or

global government), only weak countries are

under any constraint to allow international

scrutiny of their human rights performance.

For the liberal internationalist, global

institutions and values, like human rights,

matter more, although the international

system is still based on state sovereignty.

Theories of functionalism attach importance

to gradual political federation, beginning

with economic and social cooperation,

especially through regional organizations.

As these networks of interdependence grow,

sovereign authority shifts to international

institutions. Under the constructivist theory

of international relations, ideas, such as

human rights, define international structure,

which in turn defines the interests and

identities of states. Thus, social norms like

human rights, rather than national security,

can shape and progressively change foreign

policy. In sum, as Richard Falk and others

argue, absolute sovereignty has given way to

the conception of “responsible sovereignty,”

according to which sovereignty is

conditional upon the state’s demonstrable

adherence to minimum human rights

standards and capacity to protect its

citizens.

19

Charter also includes “international co-operation…in

promoting and encouraging respect for human rights”

among the purposes of the UN.

19

Richard A. Falk, Human Rights Horizons: The

Pursuit of Justice in a Globalizing World, New York:

These realist, liberal internationalist,

functionalist, and constructivist theories run

along a continuum from state-centric

approaches at one end (where national

interests prevail over any appeal to universal

human rights), to cosmopolitanism at the

other end (where identity with and support

for equal rights for all people should hold

state sovereignty in check). In practice,

states have accepted obligations to respect

and promote human rights under the UN

Charter and various human rights treaties,

whatever their motivations, and, as a result,

a regime has emerged in which human rights

have progressively become part of the

accepted standards of state behavior,

functioning effectively in some areas and

less so in others.

In order to understand this

phenomenon, it is useful to examine the

current set of recognized human rights

standards.

B. How do we know which rights are

recognized as human rights?

While it is legitimate to draw on

philosophical arguments or activist agendas

to claim any global social issue as a human

right, it is also useful to identify which

rights are officially recognized as such. The

most reliable source of the core content of

international human rights is found in the

International Bill of Human Rights, which

enumerates approximately fifty normative

propositions on which additional human

rights documents have built. Scores of

regional and UN treaties have expanded the

scope of recognized human rights, including

in specialized areas such as protection of

victims of armed conflict, workers, refugees

and displaced persons, and persons with

Routledge, 2001, p. 69.

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

9

disabilities.

The International Bill of Human Rights

enumerates five group rights, twenty-four

civil and political rights (CPR), and fourteen

economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR).

It also sets out seven principles that explain

how the rights should be applied and

interpreted.

The group rights listed in the

International Bill of Human Rights include

two rights of peoples (self-determination

and permanent sovereignty over natural

resources) and three rights of ethnic,

religious and linguistic minorities (namely,

the rights to enjoy one’s own culture, to

practice one’s own religion, and to use one’s

language).

The civil and political rights include

five relating to physical integrity (rights to

life; freedom from torture; freedom from

slavery; freedom from arbitrary arrest or

detention; and the right to humane treatment

under detention). Five other rights relate to

the individual’s autonomy of thought and

action (namely, freedom of movement and

residence; prohibition of expulsion of aliens;

freedom of thought, conscience and

religious belief; freedom of expression; and

the right to privacy). Another four rights

concern the administration of justice (non-

imprisonment for debt; fair trial—for which

16 additional rights are enumerated—; the

right to personhood under the law; and the

right to equality before the law). Six other

civil & political rights relate to participation

in civil society (freedom of assembly;

freedom of association; the right to marry

and found a family; rights of children; the

right to practice a religion; and—as an

exception to free speech—the prohibition of

war propaganda and hate speech constituting

incitement). The final sub-set of these rights

is the four relating to political participation

(namely, the right to hold public office; to

vote in free elections; to be elected to office;

and to equal access to public service).

The economic, social and cultural

rights reaffirmed in the International Bill of

Human Rights include four workers’ rights

(the right to gain a living by work freely

chosen and accepted; the right to just and

favorable conditions of work; the right to

form and join trade unions; and the right to

strike). Four others concern social protection

(social security; assistance to the family,

mothers and children; adequate standard of

living, including food, clothing and housing;

and the highest attainable level of physical

and mental health). The remaining rights are

the six concerning education and culture (the

right to education directed towards the full

development of the human personality; free

and compulsory primary education;

availability of other levels of education;

participation in cultural life; protection of

moral and material rights of creators and

transmitters of culture, and the right to enjoy

the benefits of scientific progress).

These rights are summarized in Table 1

below:

Table 1: List of human rights

Group Rights

1. Right to self-determination

2. Permanent sovereignty over natural

resources

3. Right to enjoy one’s culture

4. Right to practice one’s religion

5. Right to speak one’s language

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

10

Civil and Political Rights (CPR)

1. Right to life

2. Freedom from torture

3. Freedom from slavery

4. Freedom from arbitrary arrest/detention

5. Right to humane treatment in detention

6. Freedom of movement and residence

7. Prohibition of expulsion of aliens

8. Freedom of thought, conscience, and

religious belief

9. Freedom of expression

10. Right to privacy

11. Non-imprisonment for debt

12. Fair trial (sub-divided into 16

enumerated rights)

13. Right to personhood under the law

14. Equality before the law

15. Freedom of assembly

16. Freedom of association

17. Right to marry and found a family

18. Rights of children

19. Right to practice a religion

20. Prohibition of war propaganda and hate

speech constituting incitement

21. Right to hold office

22. Right to vote in free elections

23. Right to be elected to office

24. Equal access to public service

Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

(ESCR)

1. Right to gain a living by work freely

chosen and accepted

2. Right to just and favorable work

conditions

3. Right to form and join trade unions

4. Right to strike

5. Social security

6. Assistance to the family, mothers, and

children

7. Adequate standard of living (including

food, clothing, and housing)

8. Right to the highest attainable standard

of physical and mental health

9. Right to education towards the full

development of human personality

10. Free and compulsory primary education

11. Availability of other levels of education

12. Participation in cultural life

13. Protection of moral and material rights

of creators and transmitters of culture

14. Right to enjoy the benefits of scientific

progress

Finally, the seven principles of

application and interpretation include the

principles of (1) progressive realization of

ESCR (states must take meaningful

measures towards full realization of these

rights); (2) immediate implementation of

CPR (states have duties to respect and

ensure respect for these rights); (3) non-

discrimination applied to all rights; (4) an

effective remedy for violation of CPR; and

(5) equality of rights between men and

women. The International Bill also specifies

that (6) human rights may be subject to

limitations and derogations and that (7) the

rights in the Covenants may not be used as a

pretext for lowering an existing standard if

there is a higher one under national law.

In addition to the traditional grouping of

human rights in the two major categories of

human rights (CPR and ESCR), a third

category of “solidarity rights” or “third

generation rights” is sometimes invoked,

including the rights to development, to a

clean environment, and to humanitarian

assistance). The reasons for separating CPR

from ESCR have been questioned.

20

For

example, it is often claimed that CPR are

absolute and immutable, whereas ESCR are

relative and responsive to changing

conditions. However, all rights are

20

See Stephen P, Marks, “The Past and Future of the

Separation of Human Rights into Categories,”

Maryland Journal of International Law, vol. 24

(2009), pp. 208-241.

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

11

proclaimed on the expectation that they will

be of lasting value but in fact all have

emerged when social pressures have been

strong enough to challenge power relations

and expand the list. Consider, for example,

that torture was an accepted means of

obtaining a confession, that slavery was

widely practiced and accepted for centuries,

and that women were treated as chattel in

many societies and only received political

rights in the last century. Thus, these CPR

have not been permanent features of society.

It is also argued that CPR are to be

implemented by states immediately, may be

enforced through judicial remedies, and are

relatively cost-free since they merely require

the state to leave people alone (so-called

“negative rights”), whereas ESCR should be

implemented progressively, in accordance

with available resources, since they require

state expenditure (so-called “positive

rights”) and are not suitable for lawsuits

(“non-justiciable”). In many circumstances

this is true; however, many ESCR have been

made “justiciable” (that is, people can sue

the state if they consider that the right has

not been respected), and many CPR are not

achieved merely passively but require a

considerable investment of time and

resources (for example, to train law

enforcement officials or establish an

independent judiciary).

Another reason they are often

considered different in nature concerns

denunciation of violations, which is often

considered appropriate for CPR but should

be avoided for ESCR in favor of a more

cooperative approach to urge governments

to do all they should to realize these rights.

However, many situations arise where an

accusatory approach for dealing with CPR is

counter-productive and where it is

appropriate to refer to violations of ESCR.

So these two categories—which the UN

regards as inter-related and equally

important—are not watertight and reasons

for considering them inherently different

may be challenged. In practice, the context

dictates the most effective use of resources,

institutions, and approaches more than the

nature of the theoretical category of rights.

C. Are human rights the same for

everyone?

The claim that human rights are

universal holds that they are the same for

everyone because they are inherent in

human beings by virtue of all people being

human, and that human rights therefore

derive from nature (hence the term “natural

rights”). The UDHR refers to “the inherent

dignity and … equal and inalienable rights

of all members of the human family [as] the

foundation of freedom, justice and peace in

the world.” The American Declaration of

Independence proclaims that “all men are

created equal, that they are endowed by their

Creator with certain unalienable Rights” and

the French Declaration of 1789 refers to the

“natural, unalienable, and sacred rights of

man.”

Another basis for saying that human

rights are universal is to rely on their formal

adoption by virtually all countries that have

endorsed the UDHR or have ratified human

rights treaties. Cultural relativists claim that

human rights are based on values that are

determined culturally and vary from one

society to another, rather than being

universal.

21

There are several variants of this

position. One is the so-called “Asian values”

argument, according to which human rights

21

See Terence Turner and Carole Nagengast (eds.),

Journal of Anthropological Research, vol. 53, No. 3

(special issue on human rights) (Autumn 1997).

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

12

is a Western idea, which is at odds with the

way in which leaders in Asian societies

provide for the needs of their people without

making the individual supreme, prioritizing

instead the value of societal harmony and

the good of the collective.

22

A related view

holds that the concept of human rights is a

tool of Western imperialism used to disguise

political, economic and military ambitions

of Western nations against those in the

developing world.

23

A third is the “clash of

civilizations” argument that only the liberal

West, among the roughly seven civilizations

in the world, is capable of realizing human

rights since the other civilizations lack

sufficient sense of the individual and the

rule of law.

24

This issue of compatibility of

human rights with diverse belief systems

and religions has special geopolitical

repercussions in relation to Islam, for

22

See, for example, Bilahari Kim Hee P.S. Kausikan,

“An East Asian Approach to Human Rights,” The

Buffalo Journal of International Law. Vol. 2, pp.

263-283 (1995); Sharon K. Hom, “Re-Positioning

Human Rights Discourse on "Asian" Perspectives,”

The Buffalo Journal of International Law, vol. 3, pp.

209-233 (1996); Kim Dae Jung, “Is culture destiny?

The myth of Asia’s anti-democratic values,” Foreign

Affairs, vol. 73, pp. 189-194 (November/December

1994); Arvind Sharma, Are Human Rights Western?

A Contribution to the Dialogue of Civilizations, New

York: Oxford University Press, 2006, Conclusion,

pp. 254-269; Makau Mutua, "Savages, Victims and

Saviours: The Metaphor of Human Rights." Harvard

International Law Journal 42, pp. 201-245 (Winter

2001).

23

See, for example, Jean Bricmont, Humanitarian

Imperialism: Using Human Rights to Sell War,

Monthly Review Press, 2007, pp. 35-90; Makau

Mutua, Human Rights: A Political and Cultural

Critique Philadelphia, PA: University of

Pennsylvania Press (Pennsylvania Studies in Human

Rights), 2002, Chapter 2: “Human Rights as an

Ideology,” pp. 39-70.

24

See Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations

and the Remaking of World Order, New York: Simon

& Schuster, 1996.

example, on which views are divided

25

and

has been of considerable interest since the

“Arab Spring” of 2011, in which both

Islamic and human rights values motivated

peoples across the Middle East and North

Africa to overthrow deeply entrenched

dictatorships, with very mixed results, and

the emergence of extremist terrorist

organizations claiming to act according to

their interpretation of Islam.

26

The World Conference on Human

Rights (Vienna, June 1993) addressed the

general question of balancing universal and

cultural claims with this compromise

language:

All human rights are universal,

indivisible and interdependent and

interrelated. The international

community must treat human rights

globally in a fair and equal manner, on

the same footing, and with the same

emphasis. While the significance of

national and regional particularities and

25

See, for example, Abdullahi An-Naim (2004)

"‘The Best of Times’ and ‘The Worst of Times’:

Human Agency and Human Rights in Islamic

Societies," Muslim World Journal of Human Rights,

vol. 1: issue 1, Article 5. Available at:

http://www.bepress.com/mwjhr/vol1/iss1/art5; Bat

Ye’or, “Jihad and Human Rights Today. An active

ideology incompatible with universal standards of

freedom and equality,” National Review Online, July

1, 2002. Available at

http://www.nationalreview.com/comment/comment-

yeor070102.asp]; Mohamed Berween, “International

Bills of Human Rights; An Islamic Critique,”

International Journal of Human Rights, Vol. 7:4

October 2004, pp. 129 –142;

26

In its resolution 30/10 of 1 October 2015, the

Human Rights Council reaffirmed “that terrorism,

including the actions of the so-called Islamic State in

Iraq and the Levant (Daesh), cannot and should not

be associated with any religion, nationality or

civilization.” (para. 4)

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

13

various historical, cultural and religious

backgrounds must be borne in mind, it is

the duty of States, regardless of their

political, economic and cultural systems,

to promote and protect all human rights

and fundamental freedoms.

27

This statement nevertheless captures an

important feature of human rights today,

namely, that they are universal but must be

realized in the context of the prevailing

values of each society. To understand fully

the challenge such contextualization

represents we need to examine the means

and methods through which universally

accepted human rights are put into practice.

D. How are human rights put into

practice?

Human rights are traditionally studied

in a global context through (1) the norm-

creating processes, which result in global

human rights standards and (2) the norm-

enforcement processes, which seek to

translate laudable goals into tangible

practices. In addition, there are (3)

continuing and new challenges to the

effectiveness of this normative regime.

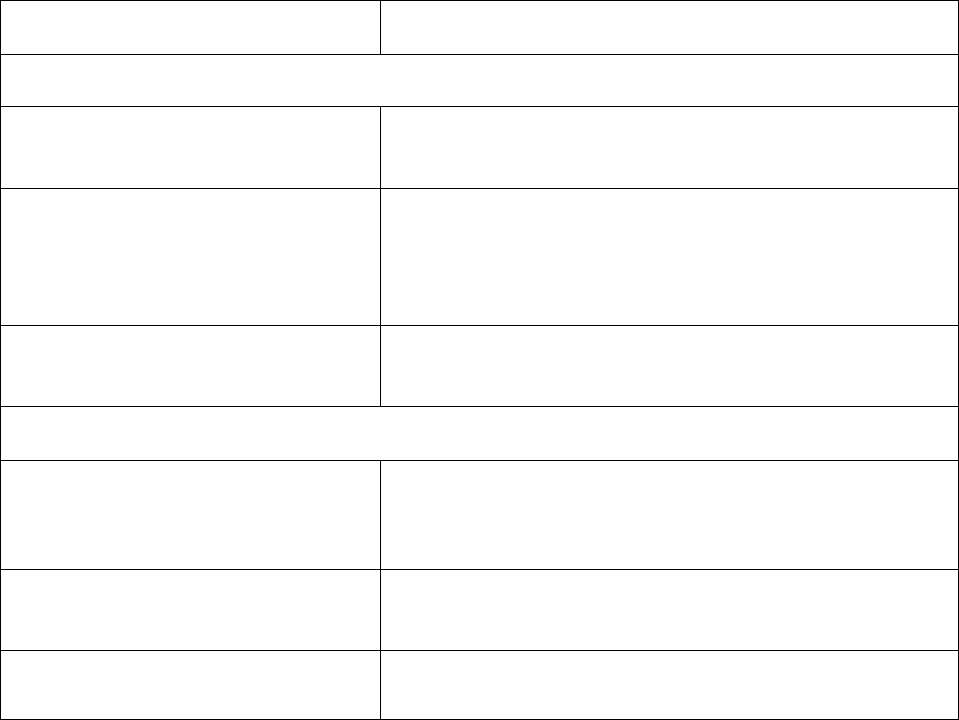

1. The norm-creating process

The norm-creating process refers to

authoritative decision-making that results in

the formal acknowledgement of specific

rights and obligations in a given society and

clarifies what is expected to realize the

rights in practice. The typical norm-creating

process in international human rights

regarding a social issue begins with

expression of concern by a delegate at a

meeting of a political body and lobbying for

co-sponsors to a resolution, which is

27

United Nations, World Conference on Human

Rights. The Vienna Declaration and Programme of

Action. June 1993, para. 5.

eventually adopted by that body. Once the

issue is on the agenda, a political body may

then commission a study, eventually leading

to drafting a declaration, and then a

convention, which has to be ratified and

enter into force and is possibly followed by

the adoption of an optional protocol

providing for complaints procedures.

All the major human rights issues, such

as torture, women’s rights, racial

discrimination, disappearances, rights of

children and of persons with disabilities,

went through these phases, lasting from ten

to thirty years or more. This is how the body

of human rights norms has expanded

considerably from the International Bill of

Human Rights to the current array of several

hundred global and regional treaties.

Following a related process, war crimes,

genocide and crimes against humanity, have

been addressed by other treaties calling for

criminal prosecutions of perpetrators.

The process can be summarized in

Table 2:

Table 2: Norm-creating process

Lobbying for a resolution by NGOs and a

limited number of government delegations

Adoption of a resolution calling for a study

Completion of a study

Adoption of a resolution calling for a declaration

Drafting and adoption of a declaration

Adoption of a resolution calling for a convention

Drafting and adoption of a convention

Ratification and entry into force of the convention

Setting up of treaty-monitoring body which

issues interpretations of obligations

Resolution calling for an optional protocol (OP)

allowing for complaints

Drafting and adoption of an OP

Ratification and entry into force of the OP

Treaty body passing judgment on complaints

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

14

2. The norm-enforcing process

Defining human rights is not enough;

measures must be taken to ensure that they

are respected, promoted and fulfilled. In the

domestic legal system, law is binding and

the courts and the police use force to compel

compliance. In the international human

rights regime, law is not treated in quite the

same way. The term “enforcement,” for

example, refers to coerced compliance,

which is rare, while most efforts focus on

“implementation”, that is, as wide range of

supervision, monitoring and general efforts

to make duty-holders accountable.

Implementation is further subdivided into

promotion (i.e., preventive measures that

seek to ensure respect for human rights in

the future) and protection (i.e., responses to

violations that have occurred in the past or

are ongoing). The means and methods of

implementation may be summarized in three

forms of promotion and five forms of

protection.

Promotion of human rights is achieved

through developing awareness, standard-

setting and interpretation, and creation of

national institutions. Awareness of human

rights is a precondition to acting on them

and is advanced though dissemination of

knowledge (e.g., publications, information

campaigns) and human rights education at

all levels. Second is standard-setting, the

drafting of human rights texts, in which the

UN Commission on Human Rights,

established in 1946, played a central role

until it was replaced in 2006 by the Human

Rights Council. Numerous other bodies in

the UN system, such as the Commission on

the Status of Women, and UN Specialized

Agencies (such as the International Labour

Organization and UNESCO), as well as the

regional organizations (Council of Europe,

Organization of American States, African

Union, League of Arab States, Association

of Southeast Asian Nations) adopt and

monitor other international human rights

texts. The third preventive or promotional

means of implementation is national

institution building, which includes

improvements in the judiciary and law

enforcement institutions and the creation of

specialized bodies such as national

commissions for human rights and offices of

an ombudsman.

The protection of human rights involves

a complex web of national and international

mechanisms to monitor, judge, urge,

denounce, and coerce states, as well as to

provide relief to victims. Monitoring

compliance with international standards is

carried out through the reporting and

complaints procedures of the UN treaty

bodies and regional human rights

commissions and courts. States are required

to submit reports and the monitoring body—

often guided by information provided by

NGOs—which examines progress and

problems with a view to guiding the

reporting country to do better. The Human

Rights Council also carries out a Universal

Periodic Review (UPR) of all countries,

regardless of treaty ratification. Several

optional procedures allow individuals and

groups (and sometimes other states) to

petition these bodies for a determination of

violations. The quasi-judicial bodies (such

as the Human Rights Committee or the

African Commission on Human and

Peoples’ Rights) utilize various forms of

fact-finding and investigation and issue their

views so that governments can take action to

live up to their human rights obligations.

“Special procedures” refer to UN

working groups, independent experts and

special rapporteurs or representatives

mandated to study countries or issues,

including taking on cases of alleged

violations, going on mission to countries and

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

15

institutions, and to report back on their

findings and request redress from

governments. The “thematic” rapporteurs

are specifically mandated to study issues

such as forced disappearances, summary

executions, torture, toxic waste, and the

rights to health, adequate food and housing.

As of 2015 there were some 41 “thematic

mandates”. In addition, there were 14

“country mandates” covering Belarus,

Cambodia, Central African Republic, Côte

d’Ivoire, Democratic People’s Republic of

Korea, Eritrea, Haiti, Islamic Republic of

Iran, Mali, Myanmar, Palestinian Territories,

Somalia, Sudan and Syrian Arab Republic.

The second means of protection is

adjudication of cases by fully empowered

courts, the main international ones being the

International Court of Justice (which can

only decide cases between states that agree

to submit their dispute to the Court), the

International Criminal Court (which can try

individuals for genocide, crimes against

humanity, war crimes and the crime of

aggression), as well as the regional courts,

namely, the European Court of Human

Rights (open to persons within the 47

member states of the Council of Europe);

the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

(open to the 25 states parties—23 active

parties—to the American Convention on

Human Rights); and the African Court of

Justice and Human Rights (open to the

African Commission on Human and

Peoples’ Rights, individuals and accredited

NGOs from those of the 54 African Union

members that have ratified the protocol

establishing the Court, numbering 30 in

2016).

Political supervision refers to the acts

of influential bodies made up of

representatives of states, including

resolutions judging the policies and

practices of states. The UN Human Rights

Council, the UN General Assembly, the

Committee of Ministers of the Council of

Europe, the Assembly of the Organization of

American States, all have adopted politically

significant resolutions denouncing

governments for violations of human rights

and demanding that they redress the

situation and often that they provide

compensation to the victims. Parliamentary

Commissions and National Human Rights

Commissions, as well as local and

international NGOs, also follow-up their

investigations with firmly worded and

politically significant demands for change.

This form of sanction may appear toothless

since it is not backed up with coercive force;

nevertheless, in practice many governments

take quite seriously the pronouncements of

such bodies and go to considerable lengths

to avoid such political “naming and

shaming,” including by improving their

human rights performance.

The seventh means of responding to

human rights violations is through

humanitarian relief or assistance. Provision

of food, blankets, tents, medical services,

sanitary assistance, and other forms of aid

save lives and improve health of persons

forcibly displaced, often as a result of large-

scale human rights violations. Refugees and

internally displaced persons come under the

protection of the UN High Commissioner

for Refugees (UNHCR), which deploys

massive amounts of aid, along with the

International Committee of the Red Cross,

the International Organization for Migration

(IOM), the United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF), the World Food Programme

(WFP), the United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP), the UN Office for the

Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

(OCHA) and other agencies, as well as

major NGOs like Oxfam, Care, and the

International Rescue Committee.

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

16

Finally, the use of coercion is available

only to the UN Security Council, which can

use its powers under Chapter VII of the UN

Charter to impose sanctions, cut off

communications, create ad hoc criminal

tribunals, and authorize the use of force by

member states or deploy UN troops to put an

end to a threat to international peace and

security, which it has on occasion

interpreted to include human rights

violations. Human rights considerations

were part of the use of Chapter VII in

Cambodia, Haiti, Somalia, Bosnia, Iraq and

other locations.

28

This forceful means of

protecting human rights is complex and can

have harmful health consequences, as has

been the case with sanctions imposed on

Haiti and Iraq in the 1990s. If used properly,

Chapter VII action can be the basis for

implementing the “Responsibility to

Protect”, a doctrine adopted at a 2005 UN

Summit that reaffirms the international

community’s role to prevent and stop

genocides, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and

crimes against humanity when a national

government fails to do so.

29

The

responsibility to protect (R2P) was explicitly

referred to in Security Council Resolutions

concerning the Great Lakes region, Sudan,

Libya, Côte d’Ivoire, Yemen, Mali, South

Sudan, Central African Republic, and

28

See Bertrand G. Ramcharan, The Security Council

and the Protection of Human Rights, Martinus

Nijhoff, 2002; Bardo Fassbender, Securing Human

Rights: Achievements and Challenges of the UN

Security Council, Published to Oxford Scholarship

Online: January 2012, publication date: 2011,

available at:

http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acp

rof:oso/9780199641499.001.0001/acprof-

9780199641499

(DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199641499.001.0001).

29

The doctrine was affirmed by the UN General

Assembly in paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005

World Summit Outcome Document and reaffirmed in

its resolution A/RES/63/308 of September 2009.

Syria,

30

but only in Darfur

31

and Libya

32

was

it used to authorize enforcement action. The

way R2P was applied in Libya explains in

part the reluctance to use it for enforcement

action in the civil war in Syria.

33

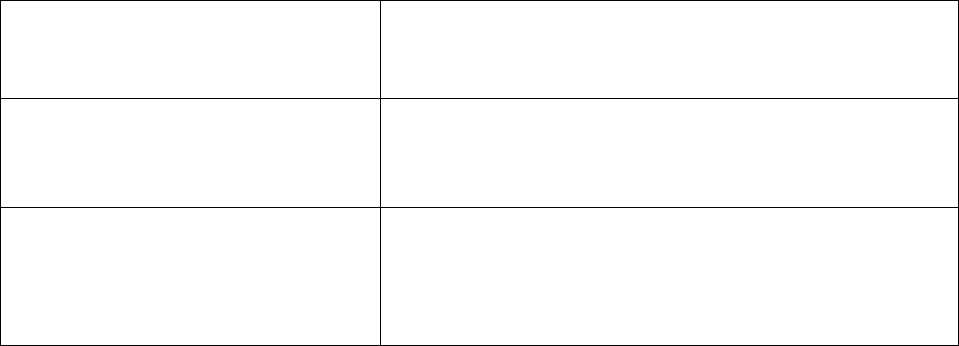

These eight means and methods of

implementation are summarized in Table 3

below.

3. Continuing and new challenges to human

rights realization

The adoption of norms and the

implementation of accountability procedures

are not enough to eliminate the deeper

causes of human rights deprivation. The

most salient challenges to the effectiveness

of human rights at the global level relate to

the reliance on the state to take

responsibility for correcting its ways;

structural issues of the global economy

favoring the maximization of profits in ways

over which human rights machinery has

little or no control or impact; and cultural

conditions based on patriarchy, class, caste

and ethnicity, which only change slowly

over time as power relations and mentalities

change. In all these arenas, human rights are

highly political: to the extent that they are

30

!For references to Responsibility to Protect (RtoP or

R2P) in Security Council Resolutions, see

http://www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/index.php/co

mponent/content/article/136-latest-news/5221--

references-to-the-responsibility-to-protect-in-

security-council-resolutions (accessed 25 Apr 2014).!

31

! Security Council Resolution 1706 of 31 August

2006.!

32

! Security Council Resolution 1970 of 26 February

2011, and Security Council Resolution 1973 of 17

March 2011.!

33

!See Spencer Zifcak, “The Responsibility to Protect

after Libya and Syria,” Melbourne Journal of

International Law, vol. 13, (2012), pp. 2-35.!

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

17

truly relevant to people’s lives they

challenge the state, the political economy

and cultural traditions. At the same time,

they offer a normative framework for

individuals and collectivities to organize for

change, so that state legitimacy is measured

by human rights performance, the political

economy is freed from gross economic

disparities and social inequities, and cultural

identity is preserved and cherished in ways

that are consistent with prevailing values of

individual autonomy and freedom. Appeals

to human rights in bringing about such

change is usually supported, at least

rhetorically, by the community of nations

and, in progressively more meaningful and

effective ways, by networks of solidarity

that have profoundly changed societies in

the past. That is how practices such as

slavery, apartheid, colonialism, and

exclusions of all sorts have been largely

eliminated. Similarly, environmental

degradation, poverty, terrorism, non-

representative government, discrimination

based on sexual orientation and an

expanding array of other challenges in the

21

st

century will continue to test the value of

human rights as a normative and

institutional guide to policy and practice.

Table 3: Means and methods of human rights implementation

Means&of&implementation!

"#$%&'()!

Promotion!

1.&Developing&awareness!

*+,-.'$/+01! 02! &.3'+-$/+01)4! %(5+$! -06(,$7(4! 8.%$1!

,+78/)!(5.-$/+019!

2.&Standard9setting&and&inter9

pretation!

:50&/+01! 02! 5(-'$,$/+01)! $15! -016(1/+01)! 3;! <=!

>.%$1! ?+78/)! *0.1-+'4! ,(7+01$'! 305+()@! 7(1(,$'!

-0%%(1/)! 3;! /,($/;! 305+()4! +1/(,&,(/$/+01! 3;!

/,+3.1$')9!

3.&Institution&building!

A.5+-+$,;!$15!'$B!(120,-(%(1/4!1$/+01$'!-0%%+))+01)!

$15!0%3.5)%$1!022+-()9!

Protection!

4.& Monitoring& compliance& with&

international&standards!

?(&0,/+17! &,0-(5.,()4! -0%&'$+1/)! &,0-(5.,()4! 2$-/C

2+15+17! $15! +16()/+7$/+014! )&(-+$'! &,0-(5.,()4!

.1+6(,)$'!&(,+05+-!,(6+(B!D<E?F9!

5.&Adjudication !

G.$)+CH.5+-+$'!&,0-(5.,()!3;!/,($/;!305+()4!H.57%(1/)!

3;!+1/(,1$/+01$'!$15!,(7+01$'!/,+3.1$')9!

6.&Political&supervision!

?()0'./+01)! H.57+17! )/$/(! &0'+-;! $15! &,$-/+-(! 3;!

+1/(,1$/+01$'! 305+()@! I1$%+17! $15! )8$%+17J! 3;!

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

18

>.%$1! ?+78/)! *0.1-+'4! <=! K(1(,$'! :))(%3';@!

5(%$,-8()4! &.3'+-! $15! &,+6$/(! )/$/(%(1/)! 3;! )/$/()!

$15!)(1+0,!022+-+$')9&

7.&Humanitarian&action!

:))+)/$1-(! /0! ,(2.7(()! $15! +1/(,1$'';! 5+)&'$-(5!

&(,)01)! +1! 8.%$1+/$,+$1! (%(,7(1-+()@! ,(&$/,+$/+01!

$15!,()(//'(%(1/9!

8.&&Coercive&action&

<=! L(-.,+/;! *0.1-+'! )$1-/+01)4! -,($/+01! 02! -,+%+1$'!

/,+3.1$')4! $15! .)(! 02! 20,-(! .15(,! /8(! 50-/,+1(! 02!

I?()&01)+3+'+/;!/0!E,0/(-/J!&(0&'(!2,0%!7(10-+5(4!B$,!

-,+%()4!(/81+-!-'($1)+17!$15!-,+%()!$7$+1)/!8.%$1+/;9!

V: Conclusion

We started by asking whether human

rights have to be considered only in legal

terms and saw that there are at least three

modes of discourse concerning human

rights: legal, philosophical and advocacy.

All three overlap, although historically

people have risen up against injustices for

millennia and made respect for dignity

integral to ethical and religious thinking,

whereas the enumeration of codes of

universal human rights has a much shorter

history, dating primarily from the 18

th

century and especially from the inaugural

moment of the UDHR in making human

rights an explicit feature of the post World

War II international legal order. We have

examined what “universal” means in a world

of conflicting ideologies, religions, beliefs

and values and reviewed the content of the

normative propositions accepted as

belonging to this category of “universal

human rights,” while sounding a cautionary

note about taking their separation into two

major categories too literally. Finally, we

examined the processes by which human

rights norms are recognized and put into

practice and referred to several challenges

facing the 21

st

century.

In the coming decades, we can expect

gaps to be filled in the institutional

machinery of Africa and Asia, and in

making ESCR genuinely equal in

importance to CPR, as well as in the

clarification of human rights standards in

such areas as sexual orientation and

advances in science and technology, while

refining the means and methods of human

rights promotion and protection. The

essential value of human rights thinking and

action, however, is unlikely to change: it has

served and will continue to serve as a gauge

of the legitimacy of government, a guide to

setting the priorities for human progress, and

a basis for consensus over what values can

be shared across diverse ideologies and

cultures.

Selected bibliography

Philip Alston and Ryan Goodman,

International Human Rights, Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2012.

Upendra Baxi, The Future of Human Rights,

2

nd

ed., New Delhi ; New York : Oxford

University Press, 2006.

Sabine C. Carey, The Politics of Human

Rights: The Quest for Dignity, Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

Andrew Clapham, Human Rights: A Very

Short Introduction (Very Short

Introductions), New York: Oxford Univ.

Press, 2007.

Jack Donnelly, International Human Rights,

4

th

edition, Westview Press, 2013.

Richard A. Falk, Human Rights Horizons:

The Pursuit of Justice in a Globalizing

World, New York: Routledge, 2001.

James Griffin, On Human Rights, Oxford,

UK: Oxford Univ. Press, 2009.

Lynn Avery Hunt and Lynn Hunt, Inventing

Human Rights: A History, New York: W.W.

Norton & Co., 2008.

Micheline Ishay (ed.), The Human Rights

Reader: Major Political Essays, Speeches,

and Documents from Ancient Times to the

Present, Second Edition, New York:

Routledge, 2007

Micheline Ishay, The History of Human

Rights: From Ancient Times to the

Globalization Era, New York: Norton and

Co., 2008.

Paul Gordon Lauren, The Evolution of

International Human Rights: Visions Seen,

3

rd

ed. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Hersch Lauterpacht, International Law and

Human Rights, with an introduction by

Isidore Silver. New York: Garland, 1950

(reprint 1973).

Daniel Moeckli, Sangeeta Shah & Sandesh

Sivakumaran International Human Rights

Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2

nd

ed. 2014.

Samuel Moyn, The Last Utopia: Human

Rights in History, Cambridge MA: Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2012.

Aryeh Neier, The International Human

Rights Movement: A History, Princeton, NY:

Princeton University Press 2012.,

James W. Nickel, Making Sense of Human

Rights, Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2007.

Margot E. Salomon, Global Responsibility

for Human Rights, Oxford, UK: Oxford

Univ. Press, 2007.

Amartya Sen, “Elements of a Theory of

Human Rights,” Philosophy & Public

Affairs, vol. 32, No. 4 (2004), pp. 315-356.

Kathryn Sikkink, The Justice Cascade: How

Human Rights Prosecutions Are Changing

World Politics (The Norton Series in World

Politics), 2011.

Beth A. Simmons, Mobilizing for Human

Rights: International Law in Domestic

Politics, New York: Cambridge Univ. Press,

2009.

Selected websites

A. Official UN sites:

1. Office of the High Commissioner for

Human Rights (UN):

http://www.ohchr.org/english/

2. World Health Organization:

http://www.who.int/hhr/en/

3. World Bank:

http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERN

AL/EXTSITETOOLS/0,,contentMDK:207496

93~pagePK:98400~piPK:98424~theSitePK:95

474,00.html

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

20

4. UNDP:

http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/li

brarypage/democratic-

governance/human_rights.html

5. UNESCO:

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-

human-sciences/themes/human-rights-based-

approach

B. Sources of human rights information:

1. University of Minnesota human rights

library (includes links to UN, other

organizations, training and education, and

centers for rehabilitation of torture survivors):

http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/

2. International Service for Human Rights:

http://www.ishr.ch/

3. Business and Human Rights:

http://www.business-humanrights.org/

4. Equipo Nizkor: http://www.derechos.org/

5. New Tactics in Human Rights:

http://www.newtactics.org/

6. Human Rights Internet (HRI):

http://www.hri.ca/

7. UPR Info: http://www.upr-info.org/en

C. Non-Governmental Organizations

1. Amnesty International:

http://www.amnesty.org/

2. The Center for Economic and Social Rights

(CESR): http://cesr.org/

3. Human Rights First:

http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/

4. Human Rights Watch: http://www.hrw.org/

5. International Commission of Jurists:

http://www.icj.org/

6. International Federation for Human Rights

(FIDH): http://www.fidh.org/

7. Peoples Movement for Human Rights

Learning: http://www.pdhre.org/

Marks Human Rights

© Harvard University 2016

21

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

M1! N(-(%3(,! OP4! OQRS! /8(! K(1(,$'! :))(%3';! 02! /8(! <1+/(5! =$/+01)! $50&/(5! $15! &,0-'$+%(5! +1!

E$,+)4! T,$1-(4! /8(! <1+6(,)$'! N(-'$,$/+01! 02! >.% $1! ?+78/)9! U/! 5(2+1()! /8(! $)&+,$/+01)! 02! /8(!

+1/(,1$/ +01 $ '!-0%% .1 +/;!/0!3(!7.+5(5!3;!+/)!VP!$,/+-'()!+1!1$/+01$'!$15!+1/(,1$/+01$'!&0'+-;9!W8+)!+)!

/8(!2.''!/(#/!02!/8(!N(-'$,$/+0 1X!

!E?":YZ["!

\8(,($)! ,(-071+/+01! 02! /8(! +18(,(1/! 5+71+/;!

$15! 02! /8(!(].$'! $15! +1$'+(1$3'(! ,+78/)!02! $''!

%(%3(,)! 02! /8(! 8.%$1! 2$%+';! +)! /8(!

20.15$/ +01 ! 0 2! 2,( (5 0 % 4! H. ) /+-( ! $ 15 ! & ( $- (! +1 !

/8(!B0,'54!

\8(,($)! 5+),(7$,5! $15! -01/(%&/! 20,! 8.%$1!

,+78/)! 8$6(!,(). '/(5! +1! 3$,3$,0.)! $-/)!B 8+-8!

8$6(! 0./,$7(5! /8(! -01)-+(1-(! 02! % $1^+154!

$15! /8(! $56(1/! 02! $! B0,'5! +1! B8+-8! 8. %$1!

3(+17)! )8$''! (1H0;! 2,((50%! 02! )&((-8! $15!

3('+(2! $15! 2,((50%! 2,0%! 2($,! $15! B$1/! 8$)!

3((1! &,0-'$+%(5! $)!/8(! 8+78()/!$)&+,$/+01!02!

/8(!-0%% 01 !&(0 &'(4!

\8(,($)! +/! +)! ())(1/+$'4! +2! %$1! +)! 10/! /0! 3(!

-0%&(''(5! /0! 8$6(! ,(-0.,)(4! $)! $! '$)/! ,()0,/4!

/0! ,(3(''+01! $7 $+1)/! /;,$11;! $1 5! 0 &&,())+014!

/8$/!8.%$1 !,+78/)!)80. '5!3( !&,0/(- /(5!3; !/8(!

,.'(!02!'$B4!

\8(,($)! +/! +)! ())(1/+$'! /0! &,0%0/(! /8(!

5(6('0&%(1/! 02! 2,+(15';! ,('$/+01)! 3(/B((1!

1$/+01)4!

\8(,($)! /8(! &(0&'()! 02! /8(! <1+/(5! =$/+01)!

8$6(! +1! /8(! *8$,/(,! ,($22+,%(5! /8(+,! 2$+/8! +1!

2.15$% ( 1 /$ '!8 . % $ 1 !, +78 /)4!+1!/8 ( !5 +7 1+/; !$15!

B0,/8!02!/8(!8.%$1!&(,)01!$15!+1!/8(!(].$'!

,+78/)! 02! %(1! $15! B0% (1! $1 5! 8$6( !

5(/(,%+1(5! /0! &,0%0/(! )0-+$'! &,07,())! $15!

3(//(,!)/$15$,5)!02!'+2(!+1!'$,7(,!2,((50%4!

\8(,($)! Y(%3(,! L/$/()! 8$6(! &'(57(5!

/8(%)('6()! /0! $ -8+(6 (4! +1! -0C0&(,$/+01! B+/8!

/8(! < 1 +/(5! =$/+01) 4! /8(! &,0%0/+01! 02!

.1+6(,)$'! ,()&(-/! 20,! $15! 03)(,6$1-(! 02!

8.%$1!,+78/)!$15!2.15$%(1/$'!2,((50%)4!

\8(,($)! $! -0%%01! .15(,)/$15+17! 02! /8()(!

,+78/)! $ 15! 2,((50%)! +)! 0 2! /8(! 7 ,($/()/!

+%&0,/ $1 - (! 20,! /8 ( ! 2.''! ,( $ '+_$ /+0 1 ! 02! /8+) !

&'(57(4!

=0B4! W8(,(20,(! W>"! K"="?:[! :LL"YZ[`!

&,0-'$+%)! W>UL! <=Ua"?L:[! N"*[:?:WUM=!

MT!><Y:=!?UK>WL!$)!$!-0%%01!)/$15$,5!02!

$-8+(6(%(1/!20,! $''! &(0&'()! $15!$''!1$/+01)4!/0!

/8(!(15!/8$/!(6(,;!+15+6+5.$'!$15!(6(, ;!0,7$1 !

02!)0-+(/;4!^((&+17!/8+)!N(-'$,$/+01!-01)/$1/';!

+1! %+1 5 4! )8$''! )/, +6( ! 3;! /($ -8 +1 7 ! $15!

(5.-$/+01!/0!&,0%0/(!,()&(-/!20,!/8()(!,+78/)!

$15! 2,((50%)! $15! 3;! &,07,())+6(! % ($).,()4!

1$/+01$'! $15! +1/(,1$/+01$'4! /0! )(-.,(! /8(+,!

.1+6(,)$'! $15! (22(-/+6(! ,(-071+/+01! $15!

03)(,6$1-(4! 30/8! $%017! /8(! &(0&'()! 02!

Y(%3(,! L/$/()! /8(%)('6()! $15! $%017! /8(!

&(0&'()!02!/(,,+/0,+()!.15(,!/8(+,!H.,+)5+-/+019!

:,/+-'(!O9!

:''!8.%$1! 3(+17)!$,(! 30,1!2,((! $15!(].$'! +1!

5+71+/;! $15! ,+78/)9! W8(;! $,(! (150B(5! B +/8!

,($)01! $1 5! -01)-+(1-(! $15! )80. '5! $-/!

/0B$,5)! 01(! $10/8(,! +1! $! )&+,+/! 02!

3,0/8(,80059!

:,/+-'(!b9!