BIENNIAL REPORT

of the

ATTORNEY GENERAL

STATE OF FLORIDA

January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016

PAM BONDI

Attorney General

Tallahassee, Florida

2017

S

T

A

T

E

O

F

F

L

O

R

I

D

A

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

G

E

N

E

R

A

L

ii

CONSTITUTIONAL DUTIES OF THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL

The revised Constitution of Florida of 1968 sets out the duties of

the Attorney General in Subsection (c), Section 4, Article IV, as:

“...the chief state legal offi cer.”

By statute, the Attorney General is head of the Department of

Legal Affairs, and supervises the following functions:

Serves as legal advisor to the Governor and other executive

offi cers of the State and state agencies;

Defends the public interest;

Represents the State in legal proceedings;

Keeps a record of his or her offi cial acts and opinions;

Serves as a reporter for the Supreme Court.

iii

S

T

A

T

E

O

F

F

L

O

R

I

D

A

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

G

E

N

E

R

A

L

STATE OF FLORIDA

OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL

PAM BONDI

March 31, 2017

The Honorable Rick Scott

Governor of Florida

The Capitol

Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0001

Dear Governor Scott:

Pursuant to my constitutional duties and the statutory

requirement that this offi ce periodically publish a report on

the Attorney General offi cial opinions, I submit herewith the

biennial report of the Attorney General for the two preceding

years from January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016.

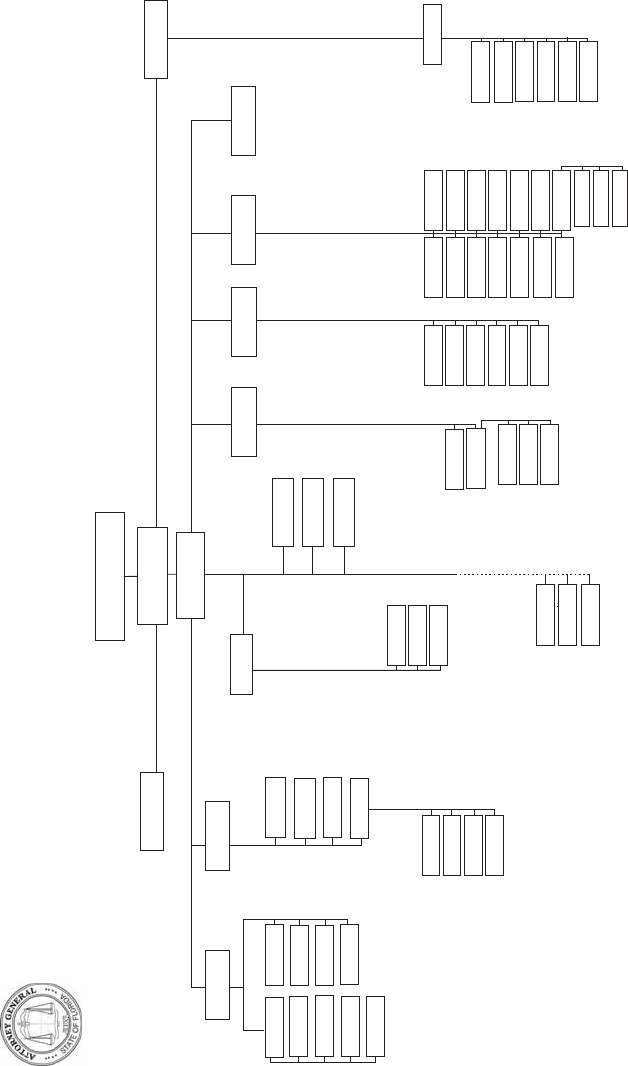

This report includes the opinions rendered, an organizational

chart, and personnel list. The opinions are alphabetically

indexed by subject in the back of the report with a table of

constitutional and statutory sections cited in the opinions.

It’s an honor to serve with you for the people of Florida.

Sincerely,

Pam Bondi

Attorney General

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Constitutional Duties of the Attorney General ....................................... ii

Letter of Transmittal .....................................................................................iii

Table of Contents ........................................................................................... iv

Attorneys General of Florida since 1845 .................................................... v

Department of Legal Affairs .........................................................................vi

Statement of Policy Concerning Attorney General Opinions ........... xii

Seal of the Attorney General of Florida ................................................ xvii

OPINIONS

Opinions 2015 ....................................................................................................1

Opinions 2016 ..................................................................................................56

INDEX AND CITATOR

General Index ................................................................................................125

Citator to Florida Statutes, Constitution,

and Session Laws ..........................................................................................135

v

ATTORNEYS GENERAL OF FLORIDA

SINCE 1845

Joseph Branch ......................................................1845-1846

Augustus E. Maxwell ...........................................1846-1848

James T. Archer ...................................................1848-1848

David P. Hogue .....................................................1848-1853

Mariano D. Papy ...................................................1853-1860

John B. Galbraith .................................................1860-1868

James D. Wescott, Jr. ...........................................1868-1868

A. R. Meek ...............................................................1868-1870

Sherman Conant ...................................................1870-1870

J. P. C. Drew ..........................................................1870-1872

H. Bisbee, Jr. ..........................................................1872-1872

J. P. C. Emmons ....................................................1872-1873

William A. Cocke ...................................................1873-1877

George P. Raney ...................................................1877-1885

C. M. Cooper...........................................................1885-1889

William B. Lamar ..................................................1889-1903

James B. Whitfi eld ................................................1903-1904

W. H. Ellis ...............................................................1904-1909

Park Trammell ......................................................1909-1913

Thomas F. West .....................................................1913-1917

Van C. Swearingen ...............................................1917-1921

Rivers Buford ........................................................1921-1925

J. B. Johnson .........................................................1925-1927

Fred H. Davis .........................................................1927-1931

Cary D. Landis.......................................................1931-1938

George Couper Gibbs ..........................................1938-1941

J. Tom Watson .......................................................1941-1949

Richard W. Ervin ..................................................1949-1964

James W. Kynes.....................................................1964-1965

Earl Faircloth ........................................................1965-1971

Robert Shevin ........................................................1971-1979

Jim Smith ...............................................................1979-1987

Robert A. Butterworth ........................................1987-2002

Richard E. Doran ................................................. 2002-2003

Charlie Crist ......................................................... 2003-2007

Bill McCollum ........................................................2007-2011

Pam Bondi ..............................................................2011-

vi

67$7(2))/25,'$

2)),&(2)7+($77251(<*(1(5$/

)/25,'$

,163(&725*(1(5$/

67$7(352*5$06

%85($8&+,()

&255(&7,216

%85($8&+,()

&,9,/5,*+76

',5(&725

$17,75867DQG

08/7,67$7(/,7,*$7,21

)/(/(&7,216&200,66,21

(;(&87,9(',5(&725

&2002167$7862):20(1

(;(&87,9(',5(&725

9,&7,06(59,&(6&5,0,1$/

-867,&(',5(&725

',52)/$:

(1)25&(0(175(/$7,216

&$3,7$/$33($/6

%85($8&+,()

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

)70<(56%85($8&+,()

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

25/$1'2%85($8&+,()

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

0,$0,%85($8&+,()

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

-$&.6219,//(%85($8&+,()

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

$667'(387<)7/$8'(5'$/(

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

7$03$%85($8&+,()

&+,/'5(16/(*$/69&6

7$03$&+,()

&+,/'5(16/(*$/69&6

)7/$8'(5'$/(&+,()

67$7(:,'(3526(&87,21

:(673$/0%&+

$'0,1,675$7,9(/$:

%85($8&+,()

&+,/'6833257

(1)25&(0(17%85($8&+,()

(&2120,&&5,0(6

08/7,67$7((1)25&(0(17&+,()

5(9(18(/,7,*$7,21

%85($8&+,()

(7+,&6

%85($8&+,()

*(1(5$/6(59,&(6

%85($8&+,()

),1$1&($1'$&&2817,1*

%85($8&+,()

+80$15(6285&(6

%85($8&+,()

(&2120,&&5,0(6

6287+)/%85($8&+,()

(&2120,&&5,0(6

&(175$/)/%85($8&+,()

(&2120,&&5,0(6

1257+)/%85($8&+,()

(&2120,&&5,0(6

',5(&725

&5,0,1$/$33($/6

:(673$/0%&+%85($8&+,()

&5,0,1$/$33($/6

0,$0,)7/$8'%85($8&+,()

&5,0,1$/$33($/6

7$//$+$66((%85($8&+,()

&5,0,1$/$33($/6

'$<721$%85($8&+,()

&5,0,1$/$33($/6

7$03$%85($8&+,()

$662&,$7('(387<

&5,0,1$/$33($/6

$662&,$7('(387<

*(1(5$/&,9,//,7,*$7,21

0(',&$,')5$8'

1257+(515(*,21$/&+,()

0(',&$,')5$8'

&(175$/5(*,21$/&+,()

0(',&$,')5$8'

6287+(515(*,21$/&+,()

9,&7,0&203(16$7,21

%85($8&+,()

&5,0,1$/-867,&(352*5$06

%85($8&+,()

$'92&$&<*5$1760*07

%85($8&+,()

&203/(;/,7,*$7,21

67$7(:,'(3526(&8725

/(*$/23,1,216

',5(&725

$77251(<*(1(5$/

&+,()'(387<

$77251(<*(1(5$/

'(387<

$77251(<*(1(5$/

7257/,7,*$7,21

%85($8&+,()

(03/2<0(17/,7,*$7,21

%85($8&+,()

'(387<

$77251(<*(1(5$/

&281&,/217+(62&,$/

67$7862)

%/$&.0(1$1'%2<6

0(',&$,')5$8'

&203/(;&,9,/(1)25&(0(17

%85($8&+,()

',5(&7252)

$'0,1,675$7,21

&,7,=(16(59,&(6

',5(&725

',5(&7252)

&$%,1(7$))$,56

',5(&7252)

&20081,&$7,216

,1)250$7,217(&+12/2*<

',5(&725

/(021/$:$5%,75$7,21

',5(&725

/$:/,%5$5<

&6(673(7(

&6()7/$8'(5'$/(

&6(7$//$+$66((

63(&,$/&2816(/)25

23(1*29(510(17

*(1(5$/&,9,/

)7/$8':3%%85($8&+,()

*(1(5$/&,9,/

7$03$%85($8&+,()

62/,&,725*(1(5$/

$662&,$7('(387<

0(',&$,')5$8'

0(',&$,')5$8'

'(387<',5(&725/$:

(1)25&(0(170$-25

',5(&7252)

/(*,6/$7,9($))$,56

23(5$7,216$1'%8'*(7

%85($8&+,()

vii

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

The Capitol, Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1050

(850) 245-0140

PAMELA BONDI

ATTORNEY GENERAL

PATRICIA CONNERS

DEPUTY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

KENT PEREZ

DEPUTY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

STEVE RUMPH JR.

INSPECTOR GENERAL

NICOLAS COX

STATEWIDE PROSECUTOR

PATRICIA GLEASON

SPECIAL COUNSEL

FOR OPEN

GOVERNMENT

EMERY GAINEY

DIRECTOR OF LAW

ENFORCEMENT

VICTIMS & CRIMINAL

JUSTICE PROGRAM

CAROLYN SNURKOWSKI

ASSOCIATE DEPUTY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

FOR CRIMINAL APPEALS

AMITABH AGARWAL

SOLICITOR GENERAL

CHESTERFIELD SMITH JR.

ASSOCIATE DEPUTY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

FOR GENERAL CIVIL

LITIGATION

DANILLE CARROLL

DIRECTOR OF CIVIL

RIGHTS

JIM VARNADO

DIRECTOR OF

MEDICAID FRAUD

SABRINA DONOVAN

DIRECTOR OF

ADMINISTRATION

VICKI BUTLER

DIRECTOR OF ECONOMIC

CRIMES

ROB JOHNSON

DIRECTOR OF

LEGISLATIVE & CABINET

AFFAIRS

DANA WIEHLE

DIRECTOR OF LEMON LAW

GERRY HAMMOND

DIRECTOR OF OPINIONS

NILDA PEDROSA

DEPUTY CHIEF OF STAFF

DOUG SMITH

DIRECTOR OF

INFORMATION SERVICES

WHITNEY RAY

COMMUNICATIONS

DIRECTOR

KIMBERLI OSWALD

DIRECTOR OF CITIZEN

SERVICES

ANDREW FAY

SPECIAL COUNSEL

JASON RODRIGUEZ

EXTERNAL AFFAIRS

viii

David Bundy

Victoria Butler

David Campbell

Leslie Campbell

James Carney

Cynthia Carrino

Danille Carroll

Edward Carter

Arlisa Certain

Maisha Champagne

Deborah Chance

Clifford Chapman

Gabrielle Charest-Turken

Emmanuela Charles

Carrol Cherry Eaton

Donna Chisholm

Maria Chisholm

Brandon Christian

Mary Clark

Rachel Clark

Katherine Cline

Brett Coleman

Robin Compton

Cynthia Comras

Jessenia Concepcion

Anne Conley

Bethany Connelly

Patricia Conners

Antony Constantini

Joseph Coronato

Carmen Corrente

James Cox

Nicholas Cox

Shelley Cridlin

Stephanie Cunningham

Stephanie Daniel

Ha Dao

Howard Dargan

Kristen Davenport

Ashley Davis

Carol DeGraffenreidt

Arielle Demby Berger

Cornelius Demps

Timothy Dennis

Robert Dietz

Joanne Diez

Jennifer Dillon

Randi Dincher

Carol Dittmar

Christina Dominguez

Vanessa Duffey

Thomas Duffy

Susan Dunlevy

Mark Dunn

Shirley Durham

David Earl

Robert Edelman

Mitchell Egber

Melissa Eggers

Robert Elson

Viviana Escobar

Diana Esposito

Eric Eves

Bilal Faruqui

Andrew Fay

Ryann Flack

David Flynn

Robert Follis

William Foster

Deborah Fraim

Colin Fraser

Timothy Fraser

Timothy Freeland

Timothy Frizzell

Anne Furlow

Sonia Garcia-Solis

Steven Gard

Cedell Garland

Sean Garvey

Jared Gass

Allan Geesey

Jeffrey Geldens

Fulvio Gentili

Donna Gerace

Jeanine Germanowicz

Walter Giffrow

Peter Gioia

Douglas Glaid

Patricia Gleason

Lisa Glick

Jonathan Glogau

Stacey Gomez-Sutter

Ely Gonzalez

Alicia Gordon

Ashley Grafton Cannon

Ashley Grant

Marcus Graper

Dayle Green

Kimberly Acuna

Jill Adams

Rotem Adar

Ronnie Adili

Amitabh Agarwal

Stephen Ake

Chelsea Alper

Jeannette Andrews-Thompson

Bianca Ankoh

Thomas Arden

Albert Arena

Alexa Argerious

David Asti

John Bajger

Samantha Josephine Baker

Stephanie Baptiste

Thomas Barnhart

Glen Bassett

Denise Beamer

Marilyn Beccue

Carla Bechard

Kenneth Beck

Berdene Beckles

Andrew Benard

Jill Bennett-Bodner

Laurie Benoit-Knox

Stephanie Bergen

Toni Bernstein

Heidi Bettendorf

James Bickner

Sofi a Bilokryla

Tabitha Blackmon

Jennifer Blanton

Laura Boeckman

Genevieve Bonan

Kayla Boone

Albert Bowden

Jessica Boxer

Anthony Bradlow

Lizabeth Brady

Ravi Brammer

Jamie Braun

Jessica Brito

Jerrett Brock

Karen Brodeen

Scott Browne

Meghan Brunette

Cindy Bruschi

Wendy Buffi ngton

ix

Diane Guillemette

Lindsey Guinand

Maria Guitian Barker

Lee Gustafson

Ellen Gwynn

Melody Hadley

Lori Hagan

Nora Hall

Mark Hamel

Christi Hankins

Denise Harle

Ginette Harrell

Virginia Harris

Lawrence Harris

Julia Harris

Jesse Haskins

Janice Haywood

Wesley Heidt

Rebecca Henderson

Kehara Hendrieth

Nikole Hiciano O’Neil

Sonya Horbelt

Sara Horowitz

Robert Humphrey

Christopher Hunt

Jonathan Hurley

Martha Hurtado

Elmer Ignacio

Lee Istrail

Jamie Ito

Clark Jennings

Kiersten Jensen

Georgina Jimenez-Orosa

Daniel Johnson

Anthony Johnson

Kristen Johnson

Caroline Johnson Levine

Bryan Jordan

Keri Joseph

Aniska Joseph

Rachael Kaiman

Linda Katz

Jennifer Keegan

Cole Kekelis

Russell Kent

Ann Keough

Anne Kingsbury

Stacey Kircher

John Klawikofsky

Jennifer Knutton

Donna Koch

Peter Koclanes

Pamela Koller

Jill Kramer

Daniel Krumbholz

Lisa Kuhlman

Jacqueline Kurland

Erik Kverne

Edmond Lambert

Kathryn Lane

Donna LaPlante

Shannon Laurie

Robert Lee

Lisa-Marie Lerner

Julia Lesh

Norman Levin

Wendy Linton

Eric Lipman

Sandra Lipman

David Llanes

Kristen Lonergan

Deborah Loucks

Christopher Lumpkin

Patrice Malloy

Madeleine Mannello Scott

Luz Maria-Montero

Julian Markham III

Leslie Marlowe

James Marsh

Lisa Martin

Paul Martin

Luis Martinez

Elba Martin-Schomaker

Cheryl Mason

Stephen Masterson

Linda Matthews

Amanda McCarthy

David McClain

Michael McDermott

Anne McDonough

Rebecca McGuigan

Amanda McKibben

Kayla McNab

Carrie McNair

James McNamara III

Donna McNulty

Melynda Melear

Michael Mervine

Stephanie Middleton

John Mika

James Millard

Jason Miller

Elizabeth Miller

Charmaine Millsaps

Robert Milne

Ilana Mitzner

Jennifer Moore

Audrey Moore

Nicole Moore

Allison Morris

Robert Morris III

Thomas Munkittrick

Teresa Mussetto

Luke Napodano

Bill Navas

Lance Neff

Betty Nestor

Kellie Nielan

Rachel Nordby

Lynette Norr

Diane Oates

Matthew Ocksrider

Mary Ottinger

Christina Pacheco

William Pafford

Robert Palmer

Paola Palou

Michelle Pardoll

Helene Parnes

Matthew Parrish

Bonnie Parrish

Trisha Pate

Wesley Paxson III

Ivy Pereira Rollins

Melka Perez

Kent Perez

Samuel Perrone

Kristen Pesicek

Robert Peterson

Chris Phillips

Lisa Phillips

Jennifer Pinder

Richard Polin

Omotayo Popoola

Lateasha Powell

Jordan Pratt

Ana Prentice

x

Sarah Prieto

Brittany Quinlan

Nicole Ramos-Barreau

Sherea Randle

Jerod Rigoni

Marie Rives

Lauren Roberson

Melissa Roca

Magaly Rodriguez

Jason Rodriguez

Don Rogers

Susan Rogers

Tonja Rook

Evan Rosen

Aimee Rosenblum

Heather Ross

Seth Rubin

Candance Sabella

Gregory Sadowski

Johnny Salgado

Alfred Saunders

Shari Scalone

Michael Schaub

Charles Schreiber Jr

Carolyn Schwarz

Jessica Schwieterman

Susan Shanahan

Tiffany Short

Sarah Shullman

Jeffrey Siegal

Holly Simcox

Darlene Simmons

Hagerenesh Simmons

Jamie Simons

Carol Simpson

Vivian Singleton

Rebecca Sirkle

Gregory Slemp

Chesterfi eld Smith Jr

Carolyn Snurkowski

Joshua Soileau

Mary Soorus

Joseph Spejenkowski

Douglas Squire

Brian Stabley

William Stafford III

Jean Stasio

Samuel Steinberg

Rachel Steinman

Marlene Stern

Paul Stevenson

Monica Stinson

Jacek Stramski

Betsy Stupski

Melanie Surber

Matthew Tannenbaum

Jonathan Tanoos

Kaylee Tatman

Cerese Taylor

Elizabeth Teegen

Edward Tellechea

Celia Terenzio

Andrew Tetreault

Courtney Thomas

Britt Thomas

Dawn Tiffi n

Andrea Totten

Sharon Traxler

Jorie Tress

Mark Urban

Alycia Vajgert

Jelica Valentine

Donna Valin

Richard Valuntas

Erin VanDeWalle

Elizabeth vandenBerg

James Varnado

Katherine Varsegi

Ann Vecchio

Marjorie Vincent-Tripp

Matthew Vitale

Kathleen Von Hoene

Rebecca Wall

Josie Warren

Shane Weaver

Nicholas Weilhammer

Brittany Weiss

Kaitlin Weiss

Marlon Weiss

W Joseph Werner

Ryann White

Dana Wiehle

Jonathan Williams

Emerald Williams

Kenneth Wilson

Blaine Winship

Anesha Worthy

Joshua Wright

Katelyn Wright

Colleen Zaczek

Jason Zapper

Danielle Zemola

xi

ASSISTANT STATEWIDE PROSECUTORS

Cynthia Avari

Diana Bock

Jonathan Bridges

Cass Castillo

Melissa Checchio

Jessica Costello

Diane Croff

Nickolaus Davis

Jessica Dobbins

Paul Dontenville

Danielle Dudai

Robert Finkbeiner

Jeremy Franker

Michael-Anthony Pica

Sylvester Polk

Carrie Pollock Gil

Priscilla Prado Stroze

John Roman

Laura Rose

Mary Sammon

James Schneider

Jeremy Scott

Julie Sercus

Joseph Spataro

Stephanie Tew

Audra Thomas-Eth

Oscar Gelpi

David Gillespie

Jennifer Gutmore

Kelsey Hellstrom

Julie Hogan

Stephen Immasche

Margery Lexa

Shannon MacGillis

Gary Malak

James McGuire

Kelly McKnight

Joanna Pang

Nicole Pegues

xii

DEPARTMENT OF LEGAL AFFAIRS

Attorney General Opinions

I. General Nature and Purpose of Opinions

Issuing legal opinions to governmental agencies has long been

a function of the Offi ce of the Attorney General. Attorney General

Opinions serve to provide legal advice on questions of statutory

interpretation and can provide guidance to public bodies as an

alternative to costly litigation. Opinions of the Attorney General,

however, are not law. They are advisory only and are not binding in a

court of law. Attorney General Opinions are intended to address only

questions of law, not questions of fact, mixed questions of fact and

law, or questions of executive, legislative or administrative policy.

Attorney General Opinions are not a substitute for the advice and

counsel of the attorneys who represent governmental agencies and

offi cials on a day to day basis. They should not be sought to arbitrate

a political dispute between agencies or between factions within an

agency or merely to buttress the opinions of an agency's own legal

counsel. Nor should an opinion be sought as a weapon by only one side

in a dispute between agencies.

Particularly diffi cult or momentous questions of law should be

submitted to the courts for resolution by declaratory judgment.

When deemed appropriate, this offi ce will recommend this course

of action. Similarly, there may be instances when

securing a

declaratory statement under the Administrative Procedure Act will

be appropriate and will be recommended.

II. Types of Opinions Issued

There are several types of opinions issued by the Attorney General's

Offi ce. All legal opinions issued by this offi ce, whether formal or

informal, are persuasive authority and not binding.

Formal numbered opinions are signed by the Attorney General

and published in the Annual Report of the Attorney General. These

opinions address questions of law which are of statewide concern.

This offi ce also issues a large body of informal opinions.

Generally these opinions address questions of more limited

application. Informal opinions may be signed by the Attorney

General or by the drafting assistant attorney general. Those

xiii

signed by the Attorney General are generally issued to public offi cials

to whom the Attorney General is required to respond. While an

offi cial or agency may request that an opinion be issued as a formal

or informal, the determination of the type of opinion issued rests with

this offi ce.

III. Persons to Whom Opinions May Be Issued

The responsibility of the Attorney General to provide legal opinions

is specifi ed in section 16.01(3), Florida Statutes, which provides:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, shall, on the written

requisition of the Governor, a member of the Cabinet, the head

of a department in the executive branch of state government,

the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the President of

the Senate, the Minority Leader of the House of Representatives,

or the Minority Leader of the Senate, and may, upon the written

requisition of a member of the Legislature, other state offi cer, or

offi cer of a county, municipality, other unit of local government,

or political subdivision, give an offi cial opinion and legal advice in

writing on any question of law relating to the offi cial duties of the

requesting offi cer.

The statute thus requires the Attorney General to render opinions

to “the Governor, a member of the Cabinet, the head of a department

in the executive branch of state government, the Speaker of the House

of Representatives, the President of the Senate, the Minority Leader of

the House of Representatives, or the Minority Leader of the Senate....”

The Attorney General may also issue opinions to “a member of the

Legislature, other state offi cer, or offi cer of a county, municipality,

other unit of local government, or political subdivision.” In addition,

the Attorney General is authorized to provide legal advice to the

state attorneys and to the representatives in Congress from this state.

Sections 16.08 and 16.52(1), Florida Statutes.

Questions relating to the powers and duties of a public board

or commission (or other collegial public body) should be requested

by a majority of the members of that body. A request from a board

should, therefore, clearly indicate that the opinion is being sought by

a majority of its members and not merely by a dissenting member or

faction.

xiv

IV. When Opinions Will Not Be Issued

Section 16.01(3), Florida Statutes, does not authorize the Attorney

General to render opinions to private individuals or entities, whether

their requests are submitted directly or through governmental

offi cials. In addition, an opinion request must relate to the requesting

offi cer's own offi cial duties. An Attorney General Opinion will not,

therefore, be issued when the requesting party is not among the

offi cers specifi ed in section 16.01(3), Florida Statutes, or when an

offi cer falling within section 16.01(3), Florida Statutes, asks a question

not relating to his or her own offi cial duties.

In order not to intrude upon the constitutional prerogative of the

judicial branch, opinions generally are not rendered on questions

pending before the courts or on questions requiring a determination

of the constitutionality of an existing statute or ordinance.

Opinions generally are not issued on questions requiring an

interpretation only of local codes, ordinances or charters rather

than the provisions of state law. Instead such requests will usually

be referred to the attorney for the local government in question. In

addition, when an opinion request is received on a question falling

within the statutory jurisdiction of some other state agency, the

Attorney General may, in the exercise of his or her discretion, transfer

the request to that agency or advise the requesting party to contact the

other agency. For example, questions concerning the Code of Ethics

for Public Offi cers and Employees may be referred to the Florida

Commission on Ethics; questions arising under the Florida Election

Code may be directed to the Division of Elections in the Department

of State.

However, as quoted above, section 16.01(3), Florida Statutes,

provides for the Attorney General's authority to issue opinions

"[n]otwithstanding any other provision of law," thus recognizing the

Attorney General's discretion to issue opinions in such instances.

Other circumstances in which the Attorney General may decline to

issue an opinion include:

• questions of a speculative nature;

• questions requiring factual determinations;

• questions which cannot be resolved due to an irreconcilable

confl ict in the laws although the Attorney General may attempt

to provide general assistance;

xv

• questions of executive, legislative or administrative policy;

• matters involving intergovernmental disputes unless all

governmental agencies concerned have joined in the request;

moot questions;

• questions involving an interpretation only of local codes,

charters, ordinances or regulations; or

• where the offi cial or agency has already acted and seeks to

justify the action.

V. Form In Which Request Should Be Submitted

Requests for opinions must be in writing and should be addressed

to:

Pam Bondi

Attorney General

Department of Legal Affairs

PL01 The Capitol

Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1050

The request should clearly and concisely state the question of law

to be answered. The question should be limited to the actual matter

at issue. Suffi cient elaboration should be provided so that it is not

necessary to infer any aspect of the question or the situation on which

it is based. If the question is predicated on a particular set of facts or

circumstances, these should be fully set out.

The response time for requests for Attorney General Opinions

has been substantially reduced. This offi ce attempts to respond to

all requests for opinions within 30 days of their receipt in this offi ce.

However, in order to facilitate this expedited response to opinion

requests, this offi ce requires that the attorneys for public entities

requesting an opinion supply this offi ce with a memorandum of law to

accompany the request. The memorandum should include the opinion

of the requesting party's own legal counsel, a discussion of the legal

issues involved, together with references to relevant constitutional

provisions, statutes, charter, administrative rules, judicial decisions,

etc.

Input from other public offi cials, organizations or associations

representing public offi cials may be requested. Interested parties

may also submit a memorandum of law and other written material

xvi

or statements for consideration. Any such material will be attached to

and made a part of the permanent fi le of the opinion request to which

it relates.

VI. Miscellaneous

This offi ce provides access to formal Attorney General Opinions

through a searchable database on the Attorney General’s website at:

myfl oridalegal.com

Persons who do not have access to the Internet and wish to obtain a

copy of a previously issued formal opinion should contact the Florida

Legal Resource Center of the Attorney General’s Offi ce. Copies of

informal opinions can be obtained from the Opinions Division of the

Attorney General's Offi ce.

As an alternative to requesting an opinion, offi cials may wish to

use the informational pamphlet prepared by this offi ce on dual offi ce-

holding for public offi cials. Copies of the pamphlet can be obtained

by contacting the Opinions Division of the Attorney General's Offi ce.

In addition, the Attorney General, in cooperation with the First

Amendment Foundation, has prepared and annually updates the

Government in the Sunshine Manual which explains the law under

which Florida ensures public access to the meetings and records of

state and local government. Copies of this manual can be obtained

through the First Amendment Foundation.

xvii

Pam Bondi

The Capitol

Tallahassee

S

T

A

T

E

O

F

F

L

O

R

I

D

A

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

G

E

N

E

R

A

L

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-01

1

BIENNIAL REPORT

of the

ATTORNEY GENERAL

State of Florida

January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016

AGO 2015-01 – January 28, 2015

PUBLIC RECORDS – EMERGENCY CALLS –

CONFIDENTIALITY – VOICE RECORDINGS

WHETHER SOUND OF CALLER’S VOICE IS CONFIDENTIAL

IDENTIFYING INFORMATION

To: The Honorable Deryl Loar, Sheriff of Indian River County

Attention: Major James G. Harpring

QUESTION:

Is the recording and sound of a voice of the caller in an E911

call requesting emergency service considered “information

which may identify any person” which is made confidential by

section 365.171, Florida Statutes?

SUMMARY:

While section 365.171(12), Florida Statues, makes confi dential

information obtained by a public agency which may identify a

person requesting emergency services or reporting an emergency

in an E911 call, there is no clear indication that the Legislature

intended to include the sound of a person’s voice as information

protected from disclosure to the public at large.

Florida’s Public Records Law, Chapter 119, Florida Statutes, provides

a right of access to the records of state and local governments, as well

as private entities acting on their behalf.

1

For purposes of the law, the

term “public records” is defi ned to include

all documents, papers, letters, maps, books, tapes, photographs,

fi lms, sound recordings, data processing software, or other

material, regardless of the physical form, characteristics,

or means of transmission, made or received pursuant to law

or ordinance or in connection with the transaction of offi cial

business by any agency.

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-01

2

The only exceptions to the requirements of the Public Records Law

are those established by general law or by the Constitution.

2

There is

no question that the sound recording of an E911 call is a public record

for purposes of the Public Records Law.

3

Section 365.171(12)(a), Florida

Statutes, however, provides:

Any record, recording, or information, or portions thereof,

obtained by a public agency or a public safety agency for the

purpose of providing services in an emergency and which

reveals the name, address, telephone number, or personal

information about, or information which may identify any

person requesting emergency service or reporting an emergency

by accessing an emergency communications E911 system is

confi dential and exempt from the provisions of s. 119.07(1) and

s. 24(a), Art. I of the State Constitution, except that such record

or information may be disclosed to a public safety agency. The

exemption applies only to the name, address, telephone number

or personal information about, or information which may

identify any person requesting emergency services or reporting

an emergency while such information is in the custody of the

public agency or public safety agency providing emergency

services. . . .

Prior to its amendment in 1990, the statute, then section 365.171(15),

Florida Statutes, merely provided confi dentiality for information

“which reveals the name, address, or telephone number of any person

requesting emergency service or reporting an emergency by accessing

an emergency telephone number ‘911’ system[.]”

4

Relying on this

language, it was concluded in Attorney General Opinion 90-43 that only

that portion of the voice recording of a “911” call relating to the name,

address, and telephone number of the person calling the emergency

telephone number “911” to report an emergency or to request emergency

assistance is exempt from the disclosure requirements of Chapter 119,

Florida Statutes. Thus, the opinion concluded that the voice recording

of a “911” call is subject to disclosure once the name, address, and

telephone number of the caller have been deleted.

Following issuance of Attorney General Opinion 90-43, the fi rst

sentence of section 365.171(15), Florida Statutes, was amended to

extend confi dentiality to certain personal, identifying information. The

legislative history for enactment of Chapter 90-305, Laws of Florida,

amending the statute, reveals that this change in subsection (15) was

intended to “[p]rovide for confi dentiality of ‘911’ recordings or portions

of such recordings when processing information requests (under the

provisions of section 119.07(1), Florida Statutes . . .) for personal

information or information which might identify a person requesting or

reporting emergency service by use of the ‘911’ number.”

5

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-01

3

This offi ce subsequently concluded that a tape recording of a “911”

call is a public record subject to disclosure and copying when in the

custody of an emergency services department, but that portion of a “911”

call containing the name, address, telephone number, and personal

information or information which might identify a person requesting

emergency service or reporting an emergency must be redacted by the

records custodian prior to disclosure.

6

The general purpose of Chapter 119, Florida Statutes, “is to open

public records to allow Florida’s citizens to discover the actions of their

government.”

7

The Public Records Act is to be liberally construed in

favor of open government, and exemptions from disclosure are to be

narrowly construed so they are limited to their stated purpose.

8

Any

doubt as to the applicability of a Public Records exemption should be

resolved in favor of disclosure rather than secrecy.

9

It is reasonable to conclude that the sound of a person’s voice “may”

identify the individual requesting emergency services or reporting

an emergency to someone who is acquainted with or related to the

caller.

10

The Legislature, however, has not chosen to specify that the

recording of an oral communication in an E911 call is protected from

disclosure. Rather, it appears that the issue was considered during the

2010 Legislative Session. Legislation was introduced in response to

a situation in which the family of an overdose victim had to endure

repeated playbacks of the 911 call reporting their son’s death.

11

Proposed Committee Bill 10-03a by the House Governmental Affairs

Policy Committee would have made confi dential any recording of a

request for emergency services or report of an emergency using the

E911 system, allowing the release of a transcript of the recording 60

days after the date of the call or by court order upon a showing of good

cause. The bill, however, died in committee. The following year, Senate

Bill 1310 sought to amend section 365.171, Florida Statutes, to provide

that if an oral recording of a 911 emergency transmission is requested,

the recording must be digitally modifi ed in order to protect the personal

identity of any person requesting emergency services or reporting an

emergency.

12

The bill was temporarily postponed while in committee

and was not addressed further.

13

Thus, while it could be asserted that the sound of a person’s voice

may identify an individual, the Legislature has considered legislation

requiring the distortion of a person’s voice requesting services or

reporting an emergency in a 911 recording and chose to not do so. This

offi ce recognizes, however, that advancements in technology to identify

a person by his or her voice may have created a need for the Legislature

to revisit the matter and would suggest that you seek legislative

clarifi cation in how best to protect the identity of an E911 caller.

Absent a clear provision for the confi dentiality or exemption of a

voice recording of the person making an E911 call, I cannot conclude

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-01

4

that section 365.171(12), Florida makes the sound of a person’s voice

“information” which would identify the caller for purposes of redacting

confi dential information from the call.

1

Article I, s. 24, Fla. Const., also recognizes a right of access to public

records of virtually all state and local governmental entities, including

the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

2

See s. 24, Art. I, Fla. Const., recognizing an exception from public

disclosure for records exempted pursuant to the section or made

confi dential by the Florida Constitution. Subsection (c) states: “The

legislature, however, may provide by general law passed by a two-thirds

vote of each house for the exemption of records from the requirements

of subsection (a) and the exemption of meetings from the requirements

of subsection (b), provided that such law shall state with specifi city the

public necessity justifying the exemption and shall be no broader than

necessary to accomplish the stated purpose of the law.”

3

See s. 119.011(12), Fla. Stat., defi ning “public records” to include:

all documents, papers, letters, maps, books, tapes, photographs,

fi lms, sound recordings, data processing software, or other

material, regardless of the physical form, characteristics,

or means of transmission, made or received pursuant to law

or ordinance or in connection with the transaction of offi cial

business by any agency.

See also Ops. Att’y Gen. Fla. 93-60 (1993) and 90-43 (1990).

4

See Ops. Att’y Gen. Fla. 95-48 (1995), 93-60 (1993), and 90-43 (1990)

(while the portion of a voice recording revealing the name, address, and

telephone number of a person reporting an emergency or requesting

assistance using a “911” number is exempt from disclosure, the public

agency is required to release the remainder of the voice recording once

the exempt material has been deleted).

5

See Final Staff Analysis & Economic Impact Statement of CS/HB 1437,

House of Representatives Committee on Community Affairs, dated June

28, 1990.

6

Op. Att’y Gen. Fla. 93-60 (1993).

7

Christy v. Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Offi ce, 698 So. 2d 1365, 1366

(Fla. 4th DCA 1997).

8

Krischer v. D’Amato, 674 So. 2d 909, 911 (Fla. 4th DCA 1996); Seminole

County v. Wood, 512 So. 2d 1000, 1002 (Fla. 5th DCA 1987), review

denied, 520 So. 2d 586 (Fla. 1988); Tribune Company v. Public Records,

493 So. 2d 480, 483 (Fla. 2d DCA 1986), review denied sub nom., Gillum

v. Tribune Company, 503 So. 2d 327 (Fla. 1987).

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-02

5

9

Tribune Company v. Public Records, supra.

10

Compare s. 817.568(1)(f)2., Fla. Stat., defi ning “[p]ersonal identifi cation

information” for purposes of the statute to include “[u]nique biometric

data, such as fi ngerprint, voice print, retina or iris image, or other unique

physical representation[.]” (e.s.)

11

See http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/news/state-regional/house-

leader-pushes-bill-to-keep-911-calls-private/nL5LM/.

12

See Bill Analysis and Fiscal Impact Statement, Florida Senate, SB

1310, dated April 3, 2011.

13

Governmental Oversight & Accountability Committee, Florida Senate,

April 5, 2011. See SB 1310 History at: http://www.fl senate.gov/Session/

Bill/2011/1310#1310/?Tab=BillHistory&_suid=140993343915700764244

8516300654.

AGO 15-02 – January 28, 2015

PUBLIC RECORDS – UNDERCOVER PERSONNEL –

EXEMPTIONS – CRIMINAL JUSTICE AGENCY

PUBLIC RECORDS EXEMPTION FOR UNDERCOVER

PERSONNEL OF CITY’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE AGENCY

To: Mr. Jeffrey A. Chudnow, Chief of Police, City of Oviedo

QUESTION:

Do the provisions of section 119.071(4)(c), Florida Statutes,

which exempt “[a]ny information revealing undercover

personnel of any criminal justice agency” authorize the City

of Oviedo to exempt from public disclosure the names of law

enforcement officers of the city who are assigned to undercover

duty when a request is made for a personnel roster of any type

(pay roster, etc.) or a listing of all law enforcement officers of

the city when the record does not identify the officers as being

assigned to undercover duty?

SUMMARY:

Pursuant to section 119.071(4)(c), Florida Statutes,

information regarding law enforcement offi cers of the city who

are assigned to undercover duty and whose names appear on

personnel rosters or other lists of all law enforcement offi cers of

the city without regard to whether the record reveals the nature

of their duties may constitute “[a]ny information revealing

undercover personnel of any criminal justice agency[.]” The

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-02

6

Legislature’s determination that such information is exempt

from disclosure and copying under the Public Records Law,

rather than making such information confi dential, conditions

the release of exempt information upon a determination by the

custodian that there is a statutory or substantial policy need for

disclosure.

Additional information contained in your request states that the

rosters or listings would not indicate that undercover activities are

being assigned by particular law enforcement offi cers or that particular

law enforcement offi cers perform undercover duty. However, the names

of undercover law enforcement offi cers are included in the general roster

or general listing of all city law enforcement offi cers.

The general purpose of Florida’s Public Records Law “is to open

public records to allow Florida’s citizens to discover the actions of their

government.”

1

While the Public Records Law is to be liberally construed

in favor of open government, exemptions from disclosure are to be

narrowly construed and limited to their stated purpose.

2

Section 119.071, Florida Statutes, provides general exemptions from

the inspection and copying requirements of Florida’s Public Records

Law. The statute containing the exemption about which you have

inquired, section 119.071(4)(c), Florida Statutes, provides:

Any information revealing undercover personnel of any

criminal justice agency is exempt from s. 119.07(1) and s. 24(a),

Art. I of the State Constitution. (e.s.)

The exemption’s applicability to “any information” suggests a broader

application of the exemption rather than a narrow one.

3

Clearly, the

names of undercover personnel would come within the scope of “any

information.” However, the information must “reveal” undercover

personnel of the criminal justice agency. The word “reveal” is generally

defi ned as “to make known; disclose;”

4

but the Legislature has provided

no additional direction as to what “reveal” may mean.

Thus, the question becomes whether the names of undercover

personnel, without any reference to the nature of the duties performed

by those offi cers would reveal the offi cers as undercover personnel. The

governmental agency claiming the benefi t of the exemption has the

burden of proving its entitlement to that exemption.

5

Florida courts and this offi ce have recognized that a distinction

exists between records which are confi dential and records which are

only exempt from the mandatory disclosure requirements in section

119.07(1), Florida Statutes.

6

As the court in WFTV, Inc. v. School Board

of Seminole,

7

stated:

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-02

7

There is a difference between records the Legislature has

determined to be exempt from The Florida Public Records

Act and those which the Legislature has determined to be

exempt from The Florida Public Records Act and confi dential.

If information is made confi dential in the statutes, the

information is not subject to inspection by the public and may

only be released to the persons or organizations designated in

the statute. . . .

If records are not confi dential but are only exempt from the

Public Records Act, the exemption does not prohibit the

showing of such information.

Thus, the exemption provided in section 119.071(4)(c), Florida

Statutes, does not absolutely prohibit the production of information

revealing undercover personnel under all circumstances.

In Attorney General Opinion 90-50, this offi ce considered those

circumstances under which information exempted pursuant to what is

now section 119.071(4)(d)2.a, Florida Statutes (providing an exemption

for home addresses, etc., of law enforcement personnel), may be released

by an agency.

8

Although the Legislature apparently chose to place the

release of this information within the discretion of the agency by making

it subject to an exemption rather than confi dentiality, in light of the

underlying purpose of the enactment, i.e., the safety of law enforcement

offi cers and their families, any such discretion by the agency must be

exercised in light of that legislative purpose. Accordingly, the opinion

concluded that in determining whether such information should be

disclosed, an agency should consider whether there is a statutory or

substantial policy need for disclosure. In the absence of a statutory

or other legal duty to be accomplished by disclosure, an agency should

consider whether the release of such information is consistent with the

purpose of the exemption.

9

Likewise, section 119.071(4)(c), Florida Statutes, exempts any

information revealing undercover personnel of any criminal justice

agency from the disclosure provisions of section 119.07(1), Florida

Statutes. By making it the subject of an exemption, the Legislature

apparently chose to place the release of this information, once it has

been determined to “reveal” undercover personnel, within the discretion

of the agency. Whether particular information may “reveal” undercover

personnel is a determination which must be made in a case-by-case

consideration of the particular situation. Once the information is

determined to be exempt, the chief of police or the city is not required

to produce this information pursuant to a public records request. The

statute makes the information revealing undercover personnel exempt

rather than confi dential and therefore would not appear to preclude the

release of such information, however, the purpose of the exemption, i.e.,

the safety of undercover personnel, must be considered in determining

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-02

8

whether such information should be released. Thus, as this offi ce has

previously advised, a custodian of such information should determine

whether there is a statutory or substantial policy need for disclosure

before releasing any information revealing undercover personnel.

In sum, it is my opinion that pursuant to section 119.071(4)(c),

Florida Statutes, information regarding law enforcement offi cers of the

city who are assigned to undercover duty and whose names appear on

personnel rosters or other lists of all law enforcement offi cers of the city

without regard to whether the record reveals the nature of their duties

may constitute “[a]ny information revealing undercover personnel of

any criminal justice agency[.]” The Legislature’s determination that

such information is exempt from disclosure and copying under the

Public Records Law, rather than making such information confi dential,

conditions the release of exempt information upon a determination by

the custodian that there is a statutory or substantial policy need for

such disclosure.

1

Christy v. Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Offi ce, 698 So. 2d 1365, 1366

(Fla. 4th DCA 1997).

2

See National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Associated Press, 18 So.

3d 1201, 1206 (Fla. 1st DCA 2009), review denied, 37 So. 3d 848 (Fla.

2010); Krischer v. D’Amato, 674 So. 2d 909, 911 (Fla. 4th DCA 1996);

Seminole County v. Wood, 512 So. 2d 1000, 1002 (Fla. 5th DCA 1987),

review denied, 520 So. 2d 586 (Fla. 1988); Tribune Company v. Public

Records, 493 So. 2d 480, 483 (Fla. 2d DCA 1986), review denied sub nom.,

Gillum v. Tribune Company, 503 So. 2d 327 (Fla. 1987).

3

The word “any” is defi ned to mean “one, a, an, or some; one or more

without specifi cation or identifi cation; . . . every; all[.]” Webster’s New

Universal Unabridged Dictionary (2003), p. 96. And see Op. Att’y Gen.

Fla. 74-311 (1974).

4

See Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary (2003), p. 1646;

and see The American Heritage Dictionary (offi ce edition 1987), p. 589.

5

See Christy v. Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Offi ce, 698 So. 2d 1365, 1367

(Fla. 4th DCA 1997); Barfi eld v. City of Ft. Lauderdale Police Department,

639 So. 2d 1012, 1015 (Fla. 4th DCA, 1994), review denied, 649 So. 2d 869

(Fla. 1994); Florida Freedom Newspapers, Inc. v. Dempsey, 478 So. 2d

1128, 1130 (Fla. 1st DCA 1985).

6

See, e.g., Ops. Att’y Gen. Fla. 07-21 (2007) (Legislature recognized a

distinction between “exempt” and “confi dential;” confi dential information

could not be revealed under any circumstances, exempt information could

be revealed at discretion of agency); 90-50 (1990).

7

874 So. 2d 48, 53 54 (Fla. 5th DCA 2004).

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-03

9

8

The exemptions in what are now ss. 119.071(4)(d)2.a. and 119.071(4)

(c), Fla. Stat., were amendments added to the statute by Ch. 79-187,

Laws of Fla., and would appear to be directed to the same purpose – the

protection of law enforcement personnel. See Title, Ch. 79-187, Laws

of Fla., “providing that certain . . . information . . . relating to . . . law

enforcement personnel . . . are exempt from disclosure provisions of the

public record law” and Inf. Op. to Amunds, dated June 8, 2012, discussing

the purpose of the exemption currently designated in s. 119.071(4)(d)2.a.,

Fla. Stat.

9

For example, in an Inf. Op. to Chief Lee Reese, Lake Worth Police

Department, dated April 25, 1989, this offi ce stated that the personnel

fi les of the City of Lake Worth Police Department which revealed the

home addresses of former law enforcement personnel could be disclosed

to the State Attorney’s Offi ce for the purpose of serving criminal witness

subpoenas by mail pursuant to s. 48.031, Fla. Stat.

AGO 15-03 – January 28, 2015

GOVERNMENT IN THE SUNSHINE LAW – SETTLEMENT –

“CONCLUSION OF LITIGATION” – DISMISSAL

WITH PREJUDICE

WHETHER EXEMPTION FOR LITIGATION STRATEGY

MEETINGS WOULD EXTEND TO TRANSCRIPTS OF CLOSED

SESSIONS WHEN CLAIM DISMISSED WITH PREJUDICE, BUT

JURISDICTION TO ENFORCE RETAINED BY COURT

To: The Honorable Bruce H. Colton, State Attorney, Nineteenth Judicial

Circuit

QUESTION:

Does a dismissal with prejudice pursuant to a settlement

agreement that confers continuing jurisdiction on the court

to enforce the terms of the settlement agreement which have

not been fulfilled by the parties operate to conclude litigation

for purposes of section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes, to permit

the release of a transcript of a settlement or litigation strategy

session closed to the public while the litigation was ongoing?

SUMMARY:

A dismissal with prejudice pursuant to a settlement agreement

that confers continuing jurisdiction on the court to enforce

the terms of the settlement agreement would operate as a

conclusion of the litigation for purposes of section 286.011(8),

Florida Statutes, making the transcript of a settlement or

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-03

10

litigation strategy session which was closed to the public while

the litigation was ongoing, open for inspection and copying.

According to your letter, a municipality within the Nineteenth Judicial

Circuit was sued. Pursuant to section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes,

the governing body of the municipality held a settlement or litigation

strategy session that was closed to the public. The municipality

subsequently reached a settlement agreement with the plaintiff. The

settlement agreement was approved by the court and the lawsuit was

dismissed with prejudice, but the court retained jurisdiction to enforce

the terms of the agreement. The terms of the agreement have not yet

been satisfi ed and you note that the parties may seek to invoke the

jurisdiction of the court to enforce the terms of the agreement. A

copy of the transcript of the closed litigation strategy session has

been requested, but the municipality is concerned that releasing the

transcript when further litigation to enforce the settlement agreement

may occur would allow the plaintiff to gain access to the transcript and

use it to its advantage in future litigation. The Nineteenth Judicial

Circuit State Attorney’s Offi ce became involved in this matter as it is

the State Attorney who is statutorily charged with investigation and

prosecution of Public Records violations.

1

You have advised this offi ce

that you have discussed your request for an Attorney General’s Opinion

with the city attorney involved in the litigation who has agreed that an

Opinion on this question would be helpful.

Discussions between a public board and its attorney are generally

subject to the requirements of the Government in the Sunshine Law,

section 286.011, Florida Statutes.

2

However, the statute provides a

limited exemption for certain discussions of pending litigation between

a public board and its attorney. As provided in the statute:

(8) Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (1), any board

or commission of any state agency or authority or any agency

or authority of any county, municipal corporation, or political

subdivision, and the chief administrative or executive offi cer of

the governmental entity, may meet in private with the entity’s

attorney to discuss pending litigation to which the entity is

presently a party before a court or administrative agency,

provided that the following conditions are met:

(a) The entity’s attorney shall advise the entity at a public

meeting that he or she desires advice concerning the litigation.

(b) The subject matter of the meeting shall be confi ned to

settlement negotiations or strategy sessions related to litigation

expenditures.

(c) The entire session shall be recorded by a certifi ed court

reporter. The reporter shall record the times of commencement

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-03

11

and termination of the session, all discussion and proceedings,

the names of all persons present at any time, and the names of

all persons speaking. No portion of the session shall be off the

record. The court reporter’s notes shall be fully transcribed and

fi led with the entity’s clerk within a reasonable time after the

meeting.

(d) The entity shall give reasonable public notice of the time

and date of the attorney client session and the names of persons

who will be attending the session. The session shall commence

at an open meeting at which the persons chairing the meeting

shall announce the commencement and estimated length of the

attorney client session and the names of the persons attending.

At the conclusion of the attorney client session, the meeting

shall be reopened, and the person chairing the meeting shall

announce the termination of the session.

(e) The transcript shall be made part of the public record upon

conclusion of the litigation. (e.s.)

When considering the construction of this provision, Florida courts

have held that the Legislature intended a strict construction of the

exemption.

3

Applying such strict construction, this offi ce concluded

that the exemption in section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes, did not

apply when no lawsuit had been fi led even though the parties involved

in the dispute believed that litigation was inevitable.

4

However, when

on-going litigation had been suspended temporarily pursuant to a

stipulation for settlement, this offi ce stated that the litigation had not

been concluded for purposes of section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes,

and therefore, a transcript of meetings held between the city and its

attorney to discuss such litigation could be kept confi dential until the

litigation was concluded.

5

Your factual situation involves transcripts of strategy sessions relating

to a complaint in an action that has been dismissed with prejudice.

This offi ce, in Attorney General Opinion 94-33, concluded that to give

effect to the purpose of section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes, a public

agency may maintain the confi dentiality of a record of a strategy or

settlement meeting between a public agency and its attorney until the

suit is dismissed with prejudice or the applicable statute of limitations

has run. That opinion involved the question of whether a voluntary

dismissal operated to conclude litigation for purposes of section

286.011(8), Florida Statutes. The plaintiff in the action had previously

fi led lawsuits against the Gainesville-Alachua County Regional Airport

Authority and voluntarily dismissed these actions after a year or two of

litigation. The airport authority was concerned that the plaintiff would

dismiss his suits, allege that the litigation was concluded, request a

copy of the transcript of strategy meetings, and then refi le the lawsuits.

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-03

12

In a subsequent opinion, Attorney General Opinion 13-13, the Citrus

County School Board was sued in federal court by three plaintiffs

who alleged that they had been denied equal access to educational

opportunities and that retaliatory action had been taken against them.

The matter was resolved between the parties and the complaint was

dismissed with prejudice by the court. Subsequently, claims were fi led

by the parents of the original plaintiffs which derived directly from

the same facts and circumstances litigated in the original lawsuit. A

request for the transcripts of the meetings between the school board

and its attorney pursuant to section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes,

was received from the parent of two of the original plaintiffs. Shortly

thereafter, a complaint against the school board was fi led in federal

court by the parents of the original plaintiffs based on the complaints

made by their daughters in the original lawsuit. The attorneys for the

Citrus County School Board asked whether the language in section

286.011(8)(e), Florida Statutes, requiring the release of transcripts of

closed meetings held to discuss settlement negotiations and litigation

expenditure strategy upon the “conclusion of the litigation” would apply

in light of the fi ling of the subsequent, derivative claim. As was noted

in Attorney General Opinion 13-13, “[i]n light of the language of section

286.011(8)(e), Florida Statutes, making the transcripts of strategy

meetings held pursuant to that section public records ‘upon conclusion

of the litigation,’ it does not appear that the Legislature intended to

recognize a continuation of the exemption for ‘derivative claims.’”

6

In a recent Second District case, Chmielewski v. City of St. Pete

Beach,

7

the court commented favorably on Attorney General Opinion

13-13 and held that a “shade meeting” transcript, prepared pursuant to

section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes, became a matter of public record

at the entry of a fi nal judgment at the conclusion of a quiet title action.

The fi nal judgment contained executory provisions which the city

characterized as enforcement proceedings resulting from the settlement

of an earlier lawsuit. The court rejected the city’s characterization

and stated that nothing in the settlement of the earlier lawsuit could

be interpreted to suggest that the quiet title lawsuit was still open,

ongoing, or capable of being reopened as to that issue. Thus, the court

held that “[t]he transcript does not regain ‘secret’ status just because a

new tangentially related lawsuit is fi led.”

8

You have advised this offi ce that a settlement agreement has been

reached and the lawsuit has been dismissed with prejudice. “Dismissed

with prejudice” is commonly understood to mean “[a] dismissal,

usually after an adjudication on the merits, barring the plaintiff from

prosecuting any later lawsuit on the same claim.”

9

While it appears

that the court has retained jurisdiction to enforce the terms of the

settlement agreement, a lawsuit on the same claim is precluded by the

dismissal with prejudice. Thus, this litigation appears to be concluded

and section 286.011(8), Florida Statutes, requires that “[t]he transcript

shall be made part of the public record upon conclusion of the litigation.”

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-03

13

(e.s.)

In sum, it is my opinion that a dismissal with prejudice pursuant to a

settlement agreement that confers continuing jurisdiction on the court

to enforce the terms of the settlement agreement would operate as a

conclusion of the litigation for purposes of section 286.011(8), Florida

Statutes, making the transcript of a settlement or litigation strategy

session which was closed to the public while the litigation was ongoing

a public record which would be open for inspection and copying.

1

See Op. Att’y Gen. Fla. 91-38 (1991) (a state attorney may prosecute

suits charging public offi cials with violations of the Public Records Act,

including those violations which may result in a fi nding of guilt for a

noncriminal infraction); and s. 119.10, Fla. Stat. (violations of Ch. 119,

Fla. Stat.).

2

See Neu v. Miami Herald Publishing Company, 462 So. 2d 821 (Fla.

1985) (s. 90.502, Fla. Stat., providing for the confi dentiality of attorney

client communications under the Florida Evidence Code, does not create

an exemption for attorney client communications at public meetings;

application of the Sunshine Law to such discussions does not usurp

Supreme Court’s constitutional authority to regulate the practice of

law, nor is it at odds with Florida Bar rules providing for attorney client

confi dentiality). Cf. s. 90.502(6), Fla. Stat., stating that a discussion or

activity that is not a meeting for purposes of s. 286.011, Fla. Stat., shall

not be construed to waive the attorney client privilege.

3

See City of Dunnellon v. Aran, 662 So. 2d 1026 (Fla. 5th DCA 1995);

and see School Board of Duval County v. Florida Publishing Company,

670 So. 2d 99 (Fla. 1st DCA 1996).

4

See Ops. Att’y Gen. Fla. 13-13 (2013), 04-35 (2004), and 98-21 (1998).

And see Ops. Att’y Gen. Fla. 06 03 (2006) (exemption not applicable to pre

litigation mediation proceedings) and 09-25 (2009) (town council which

received pre suit notice letter under the Bert J. Harris Act, s. 70.001, Fla.

Stat., is not a party to pending litigation for purposes of s. 286.011[8], Fla.

Stat.).

5

See Op. Att’y Gen. Fla. 94 64 (1994). And see Ops. Att’y Gen. Fla. 06-03

(2006) (exemption not applicable to pre litigation mediation proceedings)

and 09 25 (2009) (town council which received pre suit notice letter under

the Bert J. Harris Act, s. 70.001, Fla. Stat., is not a party to pending

litigation for purposes of s. 286.011[8], Fla. Stat.).

6

And see Op. Att’y Gen. Fla. 94-33 (1994) (a public agency may maintain

the confi dentiality of a record of a strategy or settlement meeting between

a public agency and its attorney until the suit is dismissed with prejudice

or the applicable statute of limitations has run). Cf. Op. Att’y Gen. Fla.

96-75 (1996) (disclosure of medical records to city council during closed

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-04

14

door meeting under s. 286.011(8), Fla. Stat., does not affect requirement

that transcript of such meeting be made part of public record at conclusion

of litigation).

7

161 So. 3d 521, 2014 WL 4212742 (Fla. 2d DCA 2014).

8

And see Wagner v. Orange County, 960 So. 2d 785 (Fla. 5th DCA 2007),

noting that conclusion of litigation generally occurs when fi nal judgment

is entered. The court in Wagner concluded that the phrase “conclusion

of the litigation or adversarial administrative proceedings” for purposes

of the attorney work product exemption in s. 119.071(1)(d), Fla. Stat.,

encompasses post-judgment collection efforts such as a legislative claims

bill.

9

Black’s Law Dictionary (8th ed.), p. 502.

AGO 15-04 – January 28, 2015

MUNICIPALITIES – CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTORS –

BOND

MUNICIPALITY REQUIRED TO ACCEPT ALTERNATIVE FORMS

OF SECURITY FOR PAYMENT AND PERFORMANCE BOND

To: Mr. Patrick G. Gilligan, City Attorney for the City of Ocala

QUESTION:

Does section 255.05(7), Florida Statutes, require that a

municipality accept alternate forms of security from a contractor

for public construction projects?

SUMMARY:

Section 255.05(7), Florida Statutes, authorizes a contractor

to fi le alternative forms of security with the city for public

construction projects and provides no discretion in the

municipality to refuse to accept the alternate forms of security

authorized in that subsection provided these alternate forms of

security are determined to be of suffi cient value.

According to the information you have forwarded to this offi ce, the

City of Ocala issues numerous invitations to bid for public construction

projects that require the successful bidding contractor to purchase and

provide a payment and performance bond pursuant to section 255.05,

Florida Statutes, prior to beginning construction. Subsection (7) of

the statute states that “[i]n lieu of the bond required by this section,

a contractor may fi le with the state, county, city, or other political

authority an alternative form of security in the form of cash, a money

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-04

15

order, a certifi ed check, a cashier’s check, an irrevocable letter of credit,

or a security of a type listed in part II of chapter 625.”

1

You advise that the city would prefer not to be involved in evaluating

alternate forms of security to ensure that such security satisfi es statutory

requirements and is of suffi cient value to serve the same purpose as a

bond. Further, the city would prefer that suppliers and subcontractors

in payment disputes with the contractor look to the payment bond for

compensation and not to the municipality holding the alternate form of

security.

The city has asked for this offi ce’s assistance in determining whether

it is authorized to only accept a payment and performance bond

pursuant to section 255.05(1), Florida Statutes, and to make clear in its

bid documents that it will not accept the alternate forms of security set

forth in subsection (7) of section 255.05, Florida Statutes.

Florida law has long recognized the rights of laborers, materialmen,

and subcontractors to seek payment through statutory bonding

requirements for a contractor’s failure to furnish compensation.

2

The

current statutory mechanisms for enforcing that policy are payment

and performance bonds for public works projects under section 255.05,

Florida Statutes, and payment bonds and construction liens for

private property under Part I, Chapter 713, Florida Statutes, Florida’s

“Construction Lien Law.”

3

The legislative scheme set out in section

255.05, Florida Statutes, is designed to provide protection for those

providing work and materials on public projects because a mechanic’s

lien cannot be perfected against public property.

4

Section 255.05(1), Florida Statutes, about which you have specifi cally

inquired, provides, in part, that:

A person entering into a formal contract with the state or any

county, city, or political subdivision thereof, or other public

authority or private entity, for the construction of a public

building, for the prosecution and completion of a public work,

or for repairs upon a public building or public work shall be

required, before commencing the work or before recommencing

the work after a default or abandonment, to execute and record

in the public records of the county where the improvement is

located, a payment and performance bond with a surety insurer

authorized to do business in this state as surety.

Thus, the statute requires that a contractor for the construction of a

public building or public works project generally guarantee the prompt

payment of persons who furnish labor, services, or materials through

the use of a payment bond.

The statute relating to public contractors’ bonds was patterned

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-04

16

after the federal Miller Act

5

and was intended to establish for Florida

a little Miller Act whose general aim is to equate suppliers to public

projects against which materialmen’s liens are not available with those

suppliers to private projects enjoying the security of a lien.

6

The statute

is also designed to afford protection to both the surety on the project

and the public. The bond protects the public, as project “owner,” from

two distinct defaults by a builder: the payment portion of the bond

contains the insurer’s undertaking to guarantee that all subcontractors

and materialmen will be paid and the performance part of the bond

guarantees that the contract will be fully performed.

7

Further, Florida

court’s have recognized that “section 255.05 places a corresponding duty

on the public agency, as well as the contractor, to see that a bond is in

fact posted for the protection of the subcontractors before construction

commences.”

8

As a statute designed to protect various interests, including those of

subcontractors, contractors, sureties, and the public, the straightforward

language of the statute sets forth a clear and simple method of bonding

payment for, and performance of, public construction projects.

9

Florida’s

little Miller Act is remedial in nature and thus, is entitled to a liberal

construction, within reason, to effect its intended purpose.

10

The statute

has existed as a part of the Florida Statutes since 1915.

11

Subsection (7) of section 255.05, Florida Statutes, authorizes

contractors constructing public buildings to fi le alternative forms

of security to satisfy the statutory requirements for a payment and

performance bond. Subsection (7) states:

In lieu of the bond required by this section, a contractor may

fi le with the state, county, city, or other political authority an

alternative form of security in the form of cash, a money order, a

certifi ed check, a cashier’s check, an irrevocable letter of credit,

or a security of a type listed in part II of chapter 625. Any such

alternative form of security shall be for the same purpose and

be subject to the same conditions as those applicable to the bond

required by this section. The determination of the value of an

alternative form of security shall be made by the appropriate

state, county, city, or other political subdivision.

Among the purposes of section 255.05, Florida Statutes, is the

protection of subcontractors and suppliers by providing them with an

alternative remedy to mechanics liens on public projects. Legislative

history for section 255.05, Florida Statutes, expresses the Legislature’s

intent that contractors be authorized to fi le an alternative form of

security to address the concern that:

Contractors which currently are unable to enter into

construction and repair contracts because of an inability to

obtain a perfomance [sic] bond would be able to do so, provided

BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

15-04

17

they could fi le an alternative form of security.